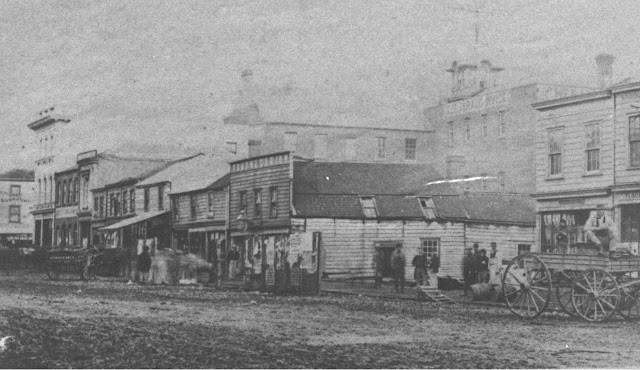

Detail from 4-53, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections

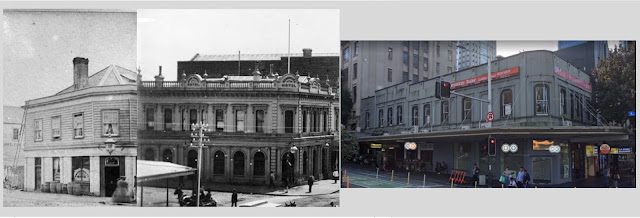

The Market Hotel mid 1860s, at the corner of Cook Street and Grey Street (later Greys Ave), Auckland. The original version dated from 1865, and the last version closed in 1969, demolished early 1970.

The originator was one Ephraim Mills, born in Gloucestershire in 1836. He arrived in Auckland in 1855, and took up work as a builder and contractor. In December 1856 he married Mary Ann Neale, daughter of Henry Neale who owned a substantial amount of land in Grey Street including part of the later Myers Park. Neales Lane was named after Mills’ father-in-law, and today is part of the Council carpark beside Mayoral Drive.

One tributary of Wai Horotiu (what I term Waihorotiu East) flowed through the gully between Queen and Grey Streets (Myers Park), then out onto Grey Street itself close to the hotel site. This was channelled by a culvert and bridge across the street to flow in behind the hotel site. Another tributary (Waihorotiu West) between Grey and Vincent Streets joined up with the eastern flow, went across Cook Street just right of the hotel site you see here, and on into what is now Aotea Square and beyond, slowing just after the crossing (also channelled and bridged) to become a swampy gully area. The Market Hotel was able to exist, as you can see here, because both bridges (dating from the early 1850s) had by 1865 become part of passable roads.

Mills had gone in for the publican business the year before with the Governor Grey Hotel, and his period with the Market Hotel, the building of which he supervised, was also brief (1865-1867). But he was certainly a colourful businessman.

In 1867, he ran foul of the regulations at the time against any form of singing, music playing or dancing in pubs. A regulation in place to stop pubs attracting people to, well, you know – drink.

“Ephraim Mills, of the Market Hotel, was charged with a breach of the 29th clause of the Licensing Act, which provides that "no person holding a publican's license under this Act shall suffer or permit any music or dancing for public entertainment to take place in the house or on the premises for which such license shall have been granted without the sanction of any two justices of the peace for the special occasion named."

“… Police-Sergeant Murphy deposed: I know defendant. He is the holder of the license for the Market Hotel, Grey-street, He produced the license to me. On Friday, 23rd August, I was in the hotel about a quarter before nine at night. I was accompanied by Constable Jackson. Before I entered I heard the sounds of music and dancing proceeding from the house. I went upstairs to a large room over the bar. There were about twenty men and two women in the room. A man named Henry Chambers were playing the piano. In the centre of the room six women and two men were dancing. At the last end of the room is a bar, and I saw liquors taken from it to the customers. The piano is at the other end on a raised platform. I sent for Mr. Mills, and he came. He said that I had spoiled his game at pool in the billiard-room. I spoke to him about the music and dancing. He said it was not with his permission. He did not say he had taken any means to prevent it. I have frequently seen music and dancing going on in the house, and have frequently cautioned Mr. Mills. He did not take any steps to prevent the music and dancing. Sometimes, they would be stopped while I was there, and as soon as my back was turned they began again. Mr. Mills did not lock up the piano, or take any measures to stop the dancing or music. He went downstairs again.

“Cross-examined by Mr. Joy: The playing had been stopped before Mills came into the room, as the man playing stopped when he saw me. I saw the people dancing when I went upstairs. I have an option which public-houses I go into. I was in three or four public-houses that night. I was in Rose's, Carter's, and Mackenzie's that night. There were musical instruments in all three. I did not lodge information against any but Mills’. I have frequently cautioned others besides Mills. They have music, but I have not seen dancing in their houses. I know a man named Macrae who keeps a public-house within a few yards of the Court-house. I was in there the night before last. I have heard music there, but I have not seen dancing. I consider Mills' the worst-conducted house in town.

“By Mr. Gillies: My reason for reporting Mills in preference to the others was because he keeps the worst-conducted house in town. I did not drive people out of the other houses into Mills'. It is easy to hear from the billiard room the music and dancing going on upstairs.

“Constable Jackson corroborated the evidence of Sergeant Murphy.

George Lawton deposed : l am barman at the London Hotel, Mr. Carter's. On the 23rd of August I was waiter in the room at Mills'. I was waiting that night in the large room upstairs. I was in that room when Sergeant Murphy and the constable came in. When they came in music was playing, and some girls and some men were dancing. The dancing had not been going on long when the constables came in, but the music had been going on for some time. I had been for some weeks in Mr. Mills' employment before. I have often seen music and dancing in that room. There was music every night. I have heard Sergeant Murphy caution Mr Mills. In the billiard room, one could hear the music and dancing. I have seen Mr Mills in the room when the music was playing and when a man was step-dancing. He never said anything about the music.

“Cross-examined by Mr Joy: l am in Mr Carter's employment now. He has a piano and music night after night. I have never seen the police in the room where the music is. There was a man step-dancing there since I have been there, but no girls dancing. He was dancing for his own amusement. There was a man-of-war's man dancing once. A man called Henry Chambers was playing the piano. I do not know that he is a professional. He did not do any waiting that night. He was not a waiter. I have received orders from Mr Mills not to allow girls to dance. I told Chambers to stop playing. I could not stop the dancing. My orders were not to allow dancing.

“By Mr. Gillies: It is an open room, fitted for dancing. If there were a few tables put in, it would stop dancing.

“This concluded the case for the prosecution.

“For the defence, Mr Joy called Henry Chambers, who deposed: I was in Mr. Mills' employment on the 23rd August. I am hired as barman. There was dancing going on when the police came in. I received orders from the last witness to stop the dancing. I have acted as waiter repeatedly in that public-house. I was not engaged professionally to play the piano. L am not a professional musician. I did not see Mr Mills in the room while the dancing was going on.

“By Mr. Gillies: I was in the habit of playing the piano in that room. Mr Mills was aware that I did so. Mrs Mills was attending to the bar downstairs while I was playing upstairs. Mr Mills did not give me orders not to play. There has been dancing on other nights. I was in the room when the police left. I re-commenced playing shortly after the police left. There was no more dancing that night.

“By the Court: There were liquors supplied while the music was going on. His Worship said that the words in the clause under which the information was laid were very stringent. [His Worship then quoted the clause, as given above.] Now, that there was music and dancing going on that night was beyond question, and that Mr Mills had no license for that was also certain. The defence apparently was that the music and dancing was not with the consent of the proprietor of the house. But evidence had been given, at all events, that the music and dancing could not have taken place without its being heard in the billiard-room; and Mills, being in that room, must have known the fact that it was taking place. One of the witnesses stated that he had received instructions not to suffer dancing, but he stated that he could not put a stop to it. There had been nothing in the evidence to show that the police were ever required to put a stop to the dancing; on the contrary, the police gave evidence that they had over and over again cautioned Mills about what was permitted in his house. The object of music in a public-house was to attract people and people never assembled at these places without drinking, and thus grist was brought to the publican's mill. There would be neither music nor dancing if it were not to encourage drinking and other vices. The case cited by Mr Gillies was very much to the point, and in passing judgment he would read a case to show how necessary it was for a publican to be careful as to how he acted, and which it was desirable they should know. … He would find the defendant guilty, and inflict a fine of £10-and costs.”

(Southern Cross, 7 September 1867)

And, on top of this – Mills was also before the Court the same day for allowing prostitutes to be in his hotel.

“Ephraim Mills was then charged with a breach of the 16th clause of the Municipal Police Act “by suffering prostitutes to be assembled in the Market Hotel." Mr. Gillies appeared for the prosecution, Mr Joy for the defence.

“Mr Gillies said the present complaint had reference to the same time as the last case and the women were some of those who were dancing. The prosecutor, however, would not press the case, on the defendant stating that he would prevent the assembling of such characters in future, and, if need be, call in the aid of the police.

“Mr Joy would undertake to say, on behalf of Mr. Mills, that in future, where he had the slightest cause of suspicion for believing that any woman was a prostitute, he would then and there have her ejected, The real difficulty was to say who were to be designated prostitutes. There were hundreds of women who were drinking in the public-houses of Auckland, and it was not easy for Mr Mills to tell who were prostitutes unless he had the evidence that was in the possession of the police. The moment the police pointed out a prostitute, she would be turned out at once.

“His Worship said he was sure the defendant would find no difficulty in getting the assistance of the police. On the occasion in question, if he had sent down to the police-station he would soon have got assistance.”

(also Southern Cross, 7 September 1867)

Mills would go on to have two bankruptcies in his career, and a period working on the Coromandel Peninsula in the early 1870s, before returning to work in Auckland, then finally leaving to live in Fiji. He died there in 1893.