When I first came upon references to the Apple Farm of East Tamaki, I thought it was interesting but would be a considerably shorter story than it has turned out to be. Instead, it has ended up being about missionaries, land deals, surveyors-turned entrepreneurs, the misuse of trust funds, the craziness of the Auckland business economy in the mid 1880s – and apples.

Updated (info on J C Cairns) 24 November 2015.

Fairburn’s claim

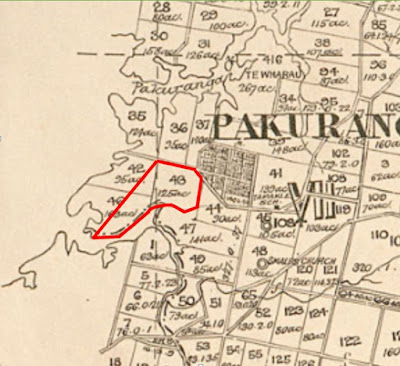

The Waiouru Peninsula in East Tamaki, east of Otahuhu, lies between the Pakuranga Creek to the north, the Tamaki Creek to the west, and the Otara Creek to the south, loosely bounded to the north-east by Ti Rakau Drive, Harris and Spring Roads.

The first European to acquire land in the area was the Church of England missionary William Thomas Fairburn (1795-1859). Albert E Tonson in his book Old Manukau (1966) refers to him as a “lay catechist,” one who laid claim to over 40,000 acres by means of direct purchase from local Maori with cash and goods totalling around £900. Further research on him and the Fairburn descendants was done by Edward Thayer Fairburn (brother of poet A R D “Rex” Fairburn, great-grandson of W T Fairburn, 1909-1998), and Rex D Evans who compiled a family history.

W T Fairburn was born 3 September 1795 in Deptford, Kent. He was in Sydney by 1817, and married Sarah Tuckwell on 12 April 1819 at Parramatta. He arrived in New Zealand with his new bride four months later, at Rangihoua in the Bay of Islands. The family returned to Sydney in 1822, then Fairburn was taken on by the CMS at their New Zealand Mission the following year , and in 1837 became the missionary at Maraetai among the Ngai Tai. He and Sarah set up early church schools, and remained resident at Maraetai until 1841.

According to Evans, William Fairburn’s grand land claim came about thus:

“Three tribes disputed the ownership of the land between Otahuhu and Papakura, a large tract of 40,000 acres. Since no natives were living on it, William [Fairburn] and Henry Williams were persuaded by the natives that, if the missionaries bought the land, they could then come back and settle peaceably upon it. Fairburn and Williams thought the idea had merit and proceeded to draw up documents for the purchase. But Henry Williams, fearing the wrath of his parent body, the CMS, backed off, leaving William to complete the deal on his own. William’s proposal to the CMS was that he would give a third of the land to the Church for farms and schools for the natives; a third was to be held in trust for the sole use of the native tribes and the other third he wished to divide amongst his now adult and landless children, all of whom had worked for years for the CMS for little or no pay … However, the CMS objected vigorously to this plan and, under threat of dismissal, William resigned from the CMS at the end of 1841.”

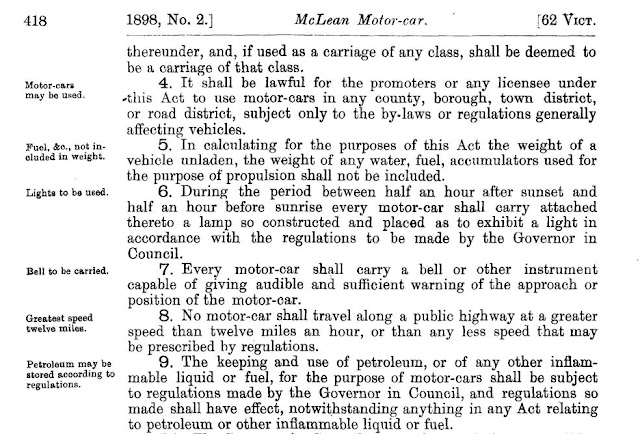

SO 931B, LINZ records crown copyright. Left, Otahuhu. Right, Fairburn's property on the Waiouru Peninsula

His first wife Sarah died in 1843. He did eventually get a Crown Grant to some of his claim, of interest to the subject of this article allotments 42, 43 and 46 of the Parish of Pakuranga in April 1844, a total of 383 acres, and part of a total 5495 acres in the area including parts of Otahuhu.

His second wife Elizabeth Newman (b.1811) died in Otahuhu in June 1847. Fairburn married a third time in 1851, to Jane Tomes. He died in Dunedin in January 1859, and his widow Jane died at the house “Ravensbourne” in Auckland in 1884.

Detail from NZ Map 4789, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries

Fairburn transferred part the land, which was to include the property known as Apple Farm (eastern part of Allotment 42, whole of 43 and eastern part of 46), to his brother-in-law Joseph Newman (1815-1892) and to his son John Fairburn in 1851 in trust for Esther Hickson née Fairburn, “to occupy and enjoy and receive and take the rents and profits” for her own unalienable use. On her death, rights passed to her husband Joseph Edward Hickson, and in trust for Esther’s children. Alfred Buckland replaced Newman as a trustee in 1858.

From 1850 this part of Fairburn’s estate was known as Otara Grove Farm, operated by Joseph Hickson. We know this because of the text of an advertisement placed by Alfred Buckland selling the property (as the Apple Farm) in September 1887, and references to the old name of the farm in the surviving Apple Farm Company file records. Hickson ran cattle and sheep there, and leased grazing to others.

The Hicksons travelled to Sydney in 1859, after the deaths of Joseph’s and Esther’s fathers, and on to England where they rented a house in Tottenham. They all returned to Auckland August 1861. Hickson leased the farm out completely from 1867 until 1873, then returned briefly, before retiring completely from farming in the late 1870s. In East Tamaki by Jennifer A Clark, 2002 (p. 77), a Whitson Powell is referred to as a lessee in 1866, but he received grants of land in Waitakere South the following year.

Theodore William (TW) Hickson … offering a farm up for apples …

Hickson’s son, surveyor and land agent Theodore William Hickson (b.1850), said to have been born on Otara Grove Farm (East Tamaki, p. 76, as well as his sister Ada Emily Hickson 1853-1934), seems to have become administrator of the property from around 1878, at a time when he lived in Pukekohe with his family. His parents now lived in the Bay of Islands, Joseph working as a land agent. T W Hickson advertised two outer paddocks on the Otara Grove property as available for grazing. (NZ Herald, 9 October 1878, p1[6]). By then, a J Murray was associated with the property, formerly used by a Mr Loverock.

T W Hickson had married Edith Jane Martin (1853-1939) on 6 January 1876. She was the daughter of Albin and Jemima Martin, owners of Allotments 35, 36 (just north-east over the road from the Apple Farm site) and 36, according to East Tamaki (p. 79), and also leased the remainder of Allotment 42 for a time from John Fairburn in 1854. (DI 2A.48)

He’d retired from government service as a surveyor in March 1881, taking up the land brokerage profession full-time. (Poverty Bay Herald, 8 March 1881, Page 3[1]). In June, he set up the Great Northern Land Agency on Queen Street, offering catalogues, mortgages, surveys and conveyancing. Later the following year, the Great Northern Land Agency name seems to have been relegated to “GNLA” beneath the larger type: “T W Hickson & Co”. Around this time, in September 1882, he published his survey map of the City of Auckland, by which he is arguably best remembered today.

NZ Map 91, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries

"The new map of Auckland city, published by Mr. T W Hickson, of the Great Northern Land Agency, is now out, and in the hands of subscribers. The map shows every allotment as fenced within the city boundaries, as well as a ground plan of every building within those limits. The material of which such building is constructed is shown by means of different colours. The position of fire-plugs, street lamps, and letter boxes, is also shown. No expense has apparently been spared in making the map as reliable and complete as possible. It has been substantially mounted, and should command a large sale amongst business men and owners of city property. Last, but perhaps not least, the map has a handsome appearance, and will form an ornament on any office wall. It is drawn upon the scale of two chains to one inch, and all the latest alterations in the city are included. The reclaimed ground around by the harbour, and the works erected thereon, are shown, and the hotels, and many of the larger places of business in the city, are recorded on the face of the map. The accuracy of the map may be depended upon, when it is remembered that Mr Hickson was for some time lnspector of Surveys, and that the map now issued was prepared from an actual survey of the city during the last 12 months. The position of the dock is shown, and even the plan of footpaths laid out in Albert Park are delineated. Mr Hickson and those he employed have evidently taken considerable trouble to secure fullness and accuracy. The map has been printed at the Herald office, and reflects credit upon the workers in that establishment."

NZ Herald, 6 September 1882, p 6

His final land brokerage ad, from September 1884, strongly advises that he intended working for investors and buyers, not vendors, and that he’d shifted offices from Queen Street to Vulcan Lane. At that point, apart from reports of his totalisator invention, nothing further is mentioned of his activities in New Zealand. Strangely, he appears to have initially abandoned his family in Auckland, taking up a surveyors licence in Australia in the 1890s, exhibiting mosquito tents and taking out various invention patents. His wife and six children joined him in South Gippsland in 1892, then the family returned to New Zealand around 1897 or 1898, according to the Fairburn family history. Theodore then left his family forever, disappearing off the records sometime after 1899. There are rumours of his association with an office in New York which caught fire, and patent records from a “T W Hickson” for various inventions. None of which seem to have led to any prominence.

Edith Hickson lived near her parents in Ellerslie from that point on, her will from 1924 referring to her husband “of parts beyond the seas.” By the time of her death in 1939, it was reported that she was then a widow, that Theodore had died “some years before”.

The Apple Farm Company forms …

Back to the early 1880s, though, when Theodore W Hickson was still present in Auckland, a successful and respected businessman, family man and land broker, with an interest (along with his sister Ada) in the old Otara Grove farm at East Tamaki. In 1880 Hickson mortgages his interest in the farm for £500 from Edward Albert Amphlett (1828-1896) “of parts beyond the seas,” the mortgage due in full on 12 February 1883. It was a deal done within the wider family. Hickson’s father-in-law Albin Martin held Amphlett’s power of attorney in 1883. Albin Martin’s daughter Mary Megellina married Amphlett at East Tamaki in 1867 (Church of St John), so Amphlett was a brother-in-law by marriage to Hickson.

So, T W Hickson owed his brother-in-law £500 for the mortgage. February 1883 came and went, and this had still not been repaid. Hickson may well have had other ideas.

In May 1882, Hickson paid his sister Ada, then living in Tasmania with her de-facto husband Harry Gardiner, £600 for her interest in the Otara Grove Farm. From then on, aside from the trustees set down by the original deed (Hickson’s parents), Hickson had full control. His uncle John Fairburn didn’t seem to have any issues – Hickson had been doing surveying and land estate work for him, as Fairburn sold off his Glengrove property in Otahuhu at this time. Buckland seemed to have only marginal involvement, at best.

Seemingly out of the blue, Hickson called together a meeting on 6 April 1883 at his Queen Street offices of nurserymen and orchardists in the Auckland region “for the promotion of fruit-growing (especially the growth of apples)”. Hickson said he’d called the meeting “on the representation of a number of fruitgrowers”. It was agreed at the meeting that a society be formed, and the names of Lippiatt, James Mason, Hawkins, John Fairburn, Dr Puchas, Parr and Sharp were named as a committee to draw up rules for a future meeting. They met again on 13 April, again at Hickson’s office, a committee named, a subscription of 5 shillings set, rules authorised and ordered to be printed. Then – nothing more.

Two days earlier, on 11 April 1883, the prospectus of the Apple Farm Company was published in the newspapers. It aimed to raise capital of £10,000 by selling 20,000 shares at 10s each, half payable on share allotment and application, the rest payable “in calls” of not more than 1s by at least 6 months intervals.

"The object of the Company is to make money by supplying a number of wants.

In California, during the months of April, May, and June, they want good fresh apples at a moderate price, and cannot got them at any price. This is a want we propose to supply.

In Auckland, they want good apples at a penny a lb. by the case, and cannot depend on getting them at anything like the price. This is another want we propose to supply.

"All over the Australian Colonies they want dried apples of good quality of local production, and cannot get them. This we mean to supply.

They also want Cider at a reasonable price all over the colonies, and cannot get it. We hope to be in a position to supply this also.

We have 200 acres of Land prepared for planting this season, and 50,000 Apple Trees, from one to four years old, ready to plant out, with 50,000 more being worked for planting next season. Our Plantation is so situated, that while we are completely out of the way of the thieving larrikin element, we are conveniently situated as regards means of conveying our fruit to market, being able to send 10 cases or 100 tons of fruit to a vessels side or deliver it in town within two hours of being picked from the trees.

The land is the best obtainable for the purpose, being a strong, friable, semi volcanic loam, slightly undulating. It is such that if the trees were planted and nothing more done but keep cattle out, they would soon produce good returns, but with good cultivation they will become rapidly productive.

It is of that consistence, and as easily undulating, that the whole of the necessary cultivation can be inexpensively effected by horse power, hand labour being required only for pruning, gathering, and packing the fruit.

"It is our intention to plant our permanent trees (Northern Spy and Majetin principally, they being blight-proof) at 30 feet apart every way in Qninceaux order, and between them, at ten feet apart every way, quicker bearing sorts, to be forced into early and exhaustive bearing, and removed or destroyed as required to make room for the growth of the permanent trees.

By this mode of planting we get over 500 trees to the acre, which will entitle us to claim £800 from the Government, under the provisions of "Tree Planting Encouragement Act," the second year from planting; the temporary trees will be forced into early and exhaustive bearing as quickly as possible, while the permanent trees will not be encouraged to fruit until well-grown.

"An immediate profit will be obtained, as it will only require an average return of 5d per tree to enable us to declare a dividend of 10 per cent per annum, after providing for all necessary expenses, and when we can get a return of 1s 9d per tree, we will be able to pay a dividend of 50 per cent, after providing for culture and erection of all necessary buildings, for packing and storing fruit, and other necessary expenses.

An average return of 12s worth of fruit per tree will enable us to pay dividends of 1000 per cent after making most liberal provision for all possible expenses. There are few trees which receive proper care and culture that will not yield considerably more than 20s worth of fruit at from six years and upwards. It being considered desirable to associate the interests of consumers with those of the producers in the undertaking as largely as possible, one-half the Company's shares are now offered to the Public."

Auckland Star, 11 April 1883, p 2(1)

On 30 April 1883, Hickson mortgaged his interest in the farm again, this time for £484 from James Cooper Cairns, due 23 July 1883. Now he owed £984 total on the property.

On 24 May 1883, a further prospectus was issued. Only 15,000 shares were to be issued, and details were given as to the land, being the old Otara Grave farm, now renamed Apple Farm, 226 acres bought via mortgage at £25 an acre. Over 50,000 trees were to be purchased from the region’s nurseries (the actual figure, although lower, still reportedly drained stocks of available apple trees from nurseries in Auckland that year) from one to five years old, but most two years old.

The new company was banking on achieving full production in five years, and that the Panama Canal would open in the next five to six years (sadly for the company’s backers, it was another 31 years before the canal was finished.)

Two days after the prospectus’ publication, all but 2,500 of the shares offered were snapped up.

The provisional directors in May 1883 were: Scots born James Cooper Cairns (1850-1919) of Mangere and Three Kings, holder of 2000 shares (largest holder) and holder of a mortgage over Hickson’s interest in the land; James Mason of Parnell; John Fairburn (son of W T Fairburn – 1824-1893) of Otahuhu; Edward Lippiatt (c.1818-1887), nurseryman also of Otahuhu; Thomas Peacock, MHR; and T W Hickson.

Under an agreement in August, Otara Grove to be acquired by Apple Farm Company for £5650 to Hickson and his parents, £650 in cash, the balance secured by mortgage.

The shareholders then were:

Cairns 2000

Hickson 2000

George Sergeant Jakins 500

James Mason 500

William Henry Connell 400

John Torrance Melville 400

By October 1883 and the first annual meeting, George Sergeant Jakins (1839-1928) and William Henry Connell had been added to the list of confirmed directors of the company. Planting had been finished, the company had all the funds it needed to meet expected expenses, the number of trees planted was 47,000 over 90 acres (planting beginning in the third week of August, and completed in three weeks), and a manager had been chosen from a number of applicants: Philip James Perry (1860-1933, also one of the largest shareholders, holding 500 shares, or the second-largest holding). William Lippiatt was to serve as Perry’s assistant and foreman. Arrangements were made to build a seven-roomed manager’s residence, along with a four-stalled stable. Part of the unused land, so it was proposed at the time, might have been planted out for a tobacco crop, but the directors turned down a similar application from a hops grower. The remainder had been leased out and planted in potatoes, oats and wheat.

The directors were quite keen on a bridge being built across the Tamaki, linking their property directly with Otahuhu and the Great South Road, saving six miles from the round trip to the city. (NZ Herald 8 October 1883, p.9)

On 27 October 1883, it all came together. Hickson’s two mortgages owed to Amphlett and Cairns were paid off; Joseph Newman replaced Buckland to become a nominal trustee for the land once more; the trustees, Joseph Edward Hickson, Esther Hickson and T W Hickson convey land to Apple Farm Company for £5650; and the Apple Farm Company mortgage taken out from T W Hickson for £5000. Hickson took out a further £5000 sub-mortgage from Fairburn and Newman, thus obtaining all the money for the land transaction early. The whole set-up was reliant on the success of the new company.

Apple varieties apparently used on the farm, as well as Northern Spy and Majetin, included Lord Sheffield, Irish Peach, Baldwin, Cambridge Pippin, and Ribston Pippin. Citrus trees were also planted. (NZ Herald 17 March 1884, p. 6) A further 1500 trees were planted in the 1884 season, and the company’s second AGM saw the directors presented with a healthy balance sheet. There weren’t even any fears regarding codlin moth, a particular concern for orchardists of the time. Perry advised that the loamy soil at East Tamaki would help protect their trees. (NZ Herald, 1 November 1884) He became a director at the 1885 AGM, a holder now of 1160 shares, topped only by Cairns at 3000, but this was disallowed at a meeting a little later on the grounds of insufficient notice, George Jakins taking his place.

By November 1884 the main shareholders were:

Cairns 3000 (up 1000)

P J Perry 1160

T H Lindsay 800

W H Simcox 800

James Mason 700 (up 200)

S A Asher 700

G S Jakins 700 (up 200)

Thomas Peacock 700

Wilson & Horton (NZ Herald proprietors) 600

Henry Brett (Auckland Star proprietor) 100

By now, Hickson had disappeared from Auckland and from New Zealand, setting himself up without his family in Australia. He had also, apparently, cashed in his shares in the company, and therefore any future pending liability.

In November 1885, Perry was charged by some of directors at an extraordinary meeting with having removed 700 trees from a piece of the farm’s land he wanted to lease. Animosity had boiled up between himself and Jakins, who led the charge to move that any offer to lease land to Perry be withdrawn. Money had been lost planting potatoes amongst the trees, the potatoes harvested being only "as big as peanuts". Some of the directors were aggrieved that by diversifying, the promised profit margin had been lost.

Perry resigned as the farm’s manager, and the first concerns were raised that the company would not have enough capital to continue. (NZ Herald 20 November 1885, p. 6) Reuben Scarborough was appointed as the new manager that month.

Cairns stepped down as chairman of the board, amid claims of profiteering.

In January 1887, in a court case between Perry and Cairns, it was revealed that Cairns had convinced Perry to take up his initial 500 shares in the company, on the understanding that if he was dismissed from the manager’s position within three years, “except on account of wilful neglect or repeated carelessness”, Cairns would buy the shares from him at the paid-up price. He demanded from Cairns a refund of money spent on the shares, immunity from liability from calls on them, and a further £250 compensation. The judge agreed that Cairns had to compensate him for the shares, interest and £25 in calls, but declined the compensation. (Auckland Star, 27 January 1887, p3)

… and the Company disintegrates

The first signs of a complete unravelling came in 1887, probably not helped by predictions such as those made by the Otago Witness that the price of apples was set to fall in the market place, and with the influx of the expected crop from the Apple Farm, the price could drop lower still. (OW, 22 April 1887 p. 11)

By June 1887, the directors were becoming worried. They met to discuss releasing the remainder of the unallotted shares to urgently raise capital. The reaction from shareholders was less than hopeful that the required £1000 would be raised to try to carry on until 1890, and that month the directors began to process of placing the company in voluntary liquidation.

The

Auckland Star remained hopeful that a new company could be formed in place of the old one, seeing as the apple trees on the farm at East Tamaki appeared to be doing so well, expected to bear 1,200 cases of fruit in the new season. Produce from the Apple Farm was even starting to win awards of merit at horticultural shows, events long dominated by fruit from Edward Lippiatt’s orchards.

By September 1887, the £5000 mortgage owed to Hickson by the Apple Farm Company was put up for sale by the Supreme Court. It was purchased by Joseph Newman, John Fairburn (Mrs Hickson’s agents) and James C Cairns for £3200. Five thousand apple trees, plus various farm implements, were put up for auction later that month. In October, the liquidator T L White sued Cairns for the amount Cairns owed on the sixth call on his shares in the company, along with fees for White’s attendance at directors meetings. Cairns lost the case. Finally, on 19 December, the Apple Farm itself was put up for auction.

The life and times of James Cooper Cairns

Caricature, Observer 24 September 1894

James Cooper Cairns was born in 1850. His father, a provisions merchant, died in Scotland apparently in 1861. In 1871, J C Cairns became eligible for a share of his father’s estate -- £3000. He married in 1874, and received £2500 in trust as part of a marriage contract. He arrived with his wife in New Zealand 1875, and used the trust money to buy a 54.5 acre farm in Mangere, today a property bounded more or less by Mountain, Miller and Coronation Roads, known as Tararata Farm. He also invested in land at Whakatane.

He returned briefly to Scotland in 1882, acquired another £100, and also received £3000 of his mother’s trust fund money, meant as an annuity fund for her until she died, on the basis that (so it was claimed) he could get better investment interest on the money in New Zealand than the trustees could back in England. On his mother’s death, it was supposed to be shared equally by him and his sister Hannah Grier Cairns. Possibly half of this money went into his investment with the Apple Farm Company (£1000 lost). Other investments would have been mortgages, land in Mt Roskill, Roganville in Mt Albert, and timberland ventures in the Waitakere Ranges and near Kaiwaka with Samuel Bradley (also a past partner of his in a shipping venture to Samoa) and Francis Mander. In his business dealings, he conveyed the impression that the funds he had to use were all his, and not those that came from long-term trust funds for his family’s benefit.

Perhaps concerned as to what was happening with her fund (she didn’t receive any sets of accounts from him, only mentions in other correspondence), Cairns’ mother arrived in Auckland in 1884. She began, slowly, to try to help her son with his investments. She did receive interest payments from him, but closer to the point of Cairn’s bankruptcy (and the end of the Apple Farm Company), the interest payments became erratic. It isn’t known whether she was ever recompensed for the lost investment money. Cairns’ bankruptcy lasted from 1888-1894. He and his family left Auckland in 1889, then returned; his wife died in Mt Albert in 1894, from apoplexy. Around 1895, he married Jessie Ritchie from Edinburgh, who came (according to the Observer) with a £50 dowery.

In 1896, Cairns appears at Norsewood, in a business "Cairns & Co", acting as local agents for an insurance company. His store burned down in April 1897, the later inquiry determining that it was arson by person or persons unknown. In the fire, among other items, Cairns claimed he lost his father's gold watch that had been in the family for 50 years. While he had the store, he was also a sawmiller at Waipawa -- and went into bankruptcy yet again in December 1897. This time, the bankruptcy only lasted until 1899.

In 1905, Cairns’ children Annie, Elizabeth, John Dewar and James took legal action in the Supreme Court against another daughter Margaret Jane Fleming, and Cairns’ second wife Jessie in Hastings, the two trustees of the original 1874 marriage contract funds (as from a court decision in the Auckland Supreme Court in 1899). All that remained of the £2500 marriage contract trust in 1902 were four mortgages to the value of £1390. After Margaret agreed to be a co-trustee, she didn’t receive any update from her father, who had sole control of the funds, as to what was happening with them, and advised her siblings of this.

Cairns died in Te Mata, Havelock North, 10 August 1919, having lived there for around 20 years, and was well-respected in the community for his views supporting temperance, his chairmanship of the local school committee which saw the community get its first school, and his stand in 1918 against conscription for farmers and farm managers. He’d contracted a cold in the winter of 1919, and couldn’t get rid of it. He complained of feeling worse that night, after talking with his family (second wife and children, first wife dying in 1894 in Auckland), a bed was made for him near the fire, and there he quietly passed away. His will left all his remaining estate to his second wife Jessie and her children. Going by that, whatever was left from the marriage agreement trust, his children from his first marriage wouldn't have seen a penny.

His mother Jane nee Couper died at Cadzow Villa, Epsom, Auckland, in 1898, leaving what remained of her estate to the family of her daughter Hannah Grier Cairns (1848-1943), who had married James Halden Torrance (1843-1884) in Scotland in 1874. By 1880 the Torrances were living in Onehunga, Torrance being a medical practitioner. They shifted to south Epsom (Cadzow Villa) where he died in 1884 (at that stage, holding 400 shares in the Apple Farm Company). Hannah kept the farm in Epsom going, ultimately subdividing it in the early 20th century. Torrance Street is named after her.

Phillip James Perry, farming expert

He was born in England in 1860, the youngest on of Rev F H Perry of Cadmore Rectory. He left school at the age of 15 to work on a farm, then around 1878 sailed to New Zealand. His career spanned from hoeing turnips on an estate he later managed, through to the Apple Farm from 1883-1885, to appointment as sub-manager (according to obituaries) of the Waikato Land Association, having charge of the first shipment of frozen meat from Auckland to England. He returned to England, was involved with the Colonial College in Suffolk, then brought out settlers back to New Zealand before the Second Anglo Boer War of 1899-1902. He ended up connected with Westland County politics, was an adviser to Richard Seddon, and retired from business in 1905. He settled in Tasmania, involved with agricultural and immigration interests there. He died 9 May 1933 at Hobart.

After the Company, but still the Apple Farm …

From NA 50/3, LINZ records, crown copyright

Local farmer John Snell Henwood (1849-1890) took over Apple Farm in March 1888, with only two mortgages remaining on the property from the sorting out of the Apple Farm investment failure, both of which were discharged in 1889. Henwood seems to have gone into a sort of partnership with Joseph Foster (who advertised 800 fruit trees for sale from the farm in August 1889), the two men running the orchard until Henwood’s death in 1890, aged 40, when he was kicked by a horse he was unharnessing at his residence on the farm. Joseph Foster may have been succeeded by John Foster.

Henwood’s widow Mary Anne (1847-1919) leased another part of the farm to George Bellingham in 1891, and again in 1893, finally selling 18 acres to the Bellinghams in 1895. In 1901, Mary Henwood sold around 37 acres of the easternmost part of the farm to David and Agnes Belle Crooks, leaving 177 acres remaining of the original farm.

This was purchased by Frank Clifton Litchfield in 1908. Litchfield renamed the farm “Ayrshire Moor”, but he sold up in 1910. (NZ Herald, 8 October 1910, p12[1])

The next owners were Charles and Hannah Clarke, New Plymouth hotelkeepers. Charles Clarke advertised in the NZ Herald in 1911 for a “married couple, wanted at once, to manage farm East Tamaki, both milkers and capable.” (9 September 1911, p.1[7]). The farm was still known as the Apple Farm when it was sold again in 1913 to Auckland farmer John Parker. He sold the farm in 1916 to Auckland tailor John Johnston; the next owner was Penrose farmer William Knox Chambers from 1919.

Chambers transferred the farm to Ross Girling Ross and William James Girling in 1925, although advertisements referring to “Ross Apple Farm” appeared from 1924.

The last references to the Apple Farm come from reports of the Pakuranga Hunt going through East Tamaki properties in 1932, and describe them following the hounds “through on to the Apple Farm.” The farm had been part of the club’s hunts from 1902.

R G Ross was to run the farm through to 1960, when Woolf Fisher bought it as part of his Ra Ora stud. So, the old Otara Grove Farm, once the scene of a massive operation for growing apples, ended up being used to grow horses, instead.