On Tuesday 9 February 1943, the readers of the NZ Herald that morning would have found this bit of news as they sipped their tea and ate their toast.

By late June 1943, however, Newell’s posthumous generosity was put under the spotlight when members of his estranged family challenged the probate of his will through the courts, under the terms of the Family Protection Act.

So, who was William Newell, a man with so much money to give,

but who had apparently left his own family out in the cold?

We need to reach back to the middle of the 19th century, when a couple living in Stalybridge, today part of Greater Manchester in England, were married in 1847: Mark Newell, a coal merchant, and Mary Farrow. Newell was originally from Drighlington, near Leeds in West Yorkshire, and by 1851 the family had set themselves up there. Our man William Newell was the seventh child of eight at that stage, born in 1857 in Drighlington.

Mark Newell’s coal merchant business, in partnership with John Farrow (possibly his wife’s relative) was going well, employing 10 men. The partnership dissolved in 1863, however, and three years later in 1866 Mark Newell was dead, at the age of 51. By 1871, all bar one of Mary’s children were working for a living, including 14 year old William Newell, who was employed in one of the wool processing factories. Somehow, though, Mary later sorted out the finances, administered the estate, kept the family together, and took up dairy farming with them just outside Leeds by 1881. It could be speculated, perhaps, that the early brush with financial uncertainty left an impression on William Newell that he carried with him for the rest of his days.

When Newell arrived in New Zealand isn’t known, but by 1885 he had set up his Sussex Square Dairy in Wellington. In March 1886 he married Lilly Amy Elizabeth Britland, and they would have five children: Florrie (1887), Frank (1890), George (1893), William Ralph (1896), and Horace Hilton (1900). Newell’s business continued to prosper. In 1887, he took over the Huntley Farm Dairy in Manners Street, Wellington, and apart from some court appearances for street skirmishes was elected Melrose Borough Councillor in 1898.

In 1903, Newell abruptly moved to Palmerston North, and took over the license of the Royal Hotel, until May 1904. It was in that year that Lilly and the four surviving children, young Frank had already died, left Newell. “We lived extremely unhappily together,” Lilly later stated in court documents. “One of the said children namely George is a complete cripple, occasioned by an attack of rheumatism when he was 3 years of age. The doctor who attended him desired the boy to go to Hospital but [William Newell] would not hear of this because of the expense involved.

“[William] was utterly without affection for me or the children; he was domineering and totally obsessed in acquiring money, and provided the children and myself with barely necessary food and clothing; a factor which in my opinion contributed largely to the ill health of the children.“Just after my said son George was born, deceased’s sister [Mary Fredericksen] came to take charge of the household; during this period the then second youngest child Frank choked with diphtheria and [William] would not allow a doctor to be called in on account of the expense and the child died [1893] …“… I left [William] in the year 1904 and took the 4 children with me … [William] agreed to give me the sum of £2000, and I was to have the children and the responsibility of bringing them up.”

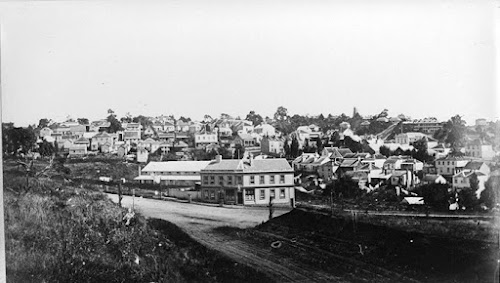

In 1907, William Newell came to Auckland and purchased Allotment 18 in Waterview, adjoining Te Auaunga/Oakley Creek and the Waitemata Harbour, from Wilhelm Paganini Hoffmann and his wife Sophia. This was the former Oakleigh Farm formerly owned by the bootmaking Garratt Brothers from 1879. Newell had a registered interest in the land from two years before, and used that to enter into a lease with a tenant named Dyke (see below). Definite sightings of William Newell in the directories and electoral rolls is difficult to prove. He may have been the William Newell, farmer, living in Bellevue Road, Mt Eden in 1911. He could have been the farmer William Newell at Burrows Ave in Parnell also in 1911. There was a farmer named William Newell living in “Kings Norton”, 8 Lower Symonds Street, in 1919.

He definitely reappears again in February 1920 when he sued Henry Vincent Dyke, to whom he leased the Oakleigh Farm in 1905. Dyke had used the land as a poultry farm, but Newell sued for £200 damages for failure to keep the farm clear of gorse and blackberry. Newell had

“…allowed the occupancy to continue until August 1918, when he gave six months' notice to terminate. He alleged that the defendant had broken up and cropped about 67 acres, but failed to comply with the terms of his agreement as to laying down that area in grass, and had also failed to cultivate, use, manure, and manage the land in a proper manner … [Newell] was a retired farmer, and lived on the income derived from letting the property, the defendant paying him a rent of £3 per week. Plaintiff had learned that the defendant had transferred his lease to another man, who now occupied the land, although plaintiff had refused to recognise him. In contravention of the lease the defendant had allowed blackberry and other weeds to flourish. … The defendant stated that he manured the property by running his poultry on it. There were never less than 12,000 to 13,000 fowls at one time, Dyke said. Practically all the ploughable area had been ploughed. In 1916 he’d laid down 47 acres in grass. When he left in 1917 a Chinese gardener was using about seven acres as a market garden. After further evidence judgment was given for the plaintiff, the amount of damages being assessed at £150, with costs.” (NZ Herald, 28 February 1920)

In 1921, Newell arranged for his Oakleigh Farm property to be subdivided; Oakley Avenue was dedicated as a public road that year. He sold the farm in sections from 1922 to 1927. By 1925, according to Newell himself in a letter to the NZ Herald, Oakley Ave had about 20 houses “and 44 ratepayers.”

He had table mortgages with some of those who had purchased property from him. In 1941, there were still four of these outstanding. At the time of his death in 1943, around half of his estate, around £10,500, was made up of debentures from territorial authorities around the country (Auckland Harbour Board, councils like Waitomo, Napier, Eltham, Mt Albert, Hauraki Plains, Whangarei, Auckland City, Otahuhu, Mt Eden, Hawkes Bay Electric Power Board, the Auckland Transport Board) and shares in the likes of Auckland Gas Company and Amalgamated Brick and Pipe.

From 1904 until 1927, Lilly raised the family. According to her statement, “I was able [with the £2000] and by small speculations in household property in Palmerston North to bring the children up. I did my best to see they all had a good education. I had my crippled son George taught music and for a period he was able to teach music himself but later on his complaint made him quite incapable of using his hands or arms.

“[William Newell] … during this time … made 4 trips to England unaccompanied by any family members. He did stay at my house on 2 or 3 occasions when on his way to make these trips or on returning from them but marital relations between us were not resumed. [He] displayed no interest whatever in the children; he was always a hard, unsympathetic and avaricious man.”

In 1927, William Newell was living in “Oakley House”, somewhere close to his subdivision on Great North Road. From 1930, when a couple to whom he had sold the property at 6 Oakley Ave defaulted on their mortgage with him, he moved in and lived there until his death. He asked Lilly to come live with him again to look after him – and she agreed. In her words,

“From then until the year 1942 when I again left [him] his attitude of mind and his dominating and penurious attributes made life extremely difficult. Finally my health was completely undermined and I was compelled to leave [him] … I returned to Palmerston North to live with and look after my crippled son George.”

For his part, William Newell left a brief opinion on his wife from this time, in a letter written to Robert King, Trust Manager with NZ Insurance Company, September 1942.

“It is with regret I write these few lines to say my wife and I has [sic] not been living happily and agreeably as husband and wife should live for many years. First, she is a fanatic on religion, very ill disposed, contrary by nature, very disagreeable on many questions. On many occasions she would raise an argument on trivial questions not worth notice, and very often would use offensive remarks in these arguments. Briefly we were badly suited to marry … what is here said is enough on our domestic troubles. She left me without any warning.”

For a viewpoint from outside the family, we do have the recollections of Mrs Florence Little, a housekeeper Newell employed to look after him, and who was with him at the end of his life. She was a beneficiary in his last will, receiving the title to 6 Oakley Avenue. Newell described her (again, in a letter to King): “… the housekeeper I now have is a very sensible intelligent and most agreeable woman, a well educated person, a first class cook, and good house manager well experienced in house work. She is a widow who [sic] husband died comparatively young. She has moderate sensible views on religion. She is a great help to me in many ways, even in the garden work.”

Florence’s own view, via her affidavit:

“I did everything about the house, inside and outside, including the lawns, garden and cutting the hedges … the last two weeks were particularly unpleasant. The last two weeks he was unable to move, and had no control over his bowels, and I had to do everything for him, carrying him from room to room about the house …“Shortly after the death … I had a nervous breakdown as a result of the strain of work and nursing and am now receiving medical attention.”

In another statement, she wrote:

“I acted as the said deceased’s housekeeper from about the beginning of August 1942 until his death on the 4th January 1943 … he informed me that he had engaged two housekeepers since his wife had left him, but one had remained only two weeks and the other only one week.”

In Newell’s original will, dated 7 November 1941, he allowed for Lilly Newell to have the house at 6 Oakley Avenue, the payments from the outstanding table mortgages he owned, £3 per week allowance, and allowances to be paid quarterly and in equal shares from all remaining income for fifteen years to his four children. After Lilly had died, everything was to be settled up and divided among the children.

Then, after Lilly left him again, Newell changed his will. Now, he left each of the four surviving children just £1000. To his wife Lilly, an increased £4 per week lifetime payment as per a new will in May 1942 was reduced back to £3. He recorded in a handwritten note that he had already been sending a sum to her during his lifetime to cover her household expenses. After Lilly’s death, the estate would be realised and divided up between, not the children, but the NZ Institute for the Blind, the Wilson Home for Crippled Children and the Church of England Orphan Home Trust.

Supreme Court Justice John Bartholomew Callan (1882-1951) made his ruling on 28 June 1944. “It is a fair inference,” Justice Callan wrote,

“that the testator changed his Will not out of any deep interest in any of the three charities, but in order to punish his wife and children for conduct as to which, upon the affadavits, they were not in the wrong. This however does not justify the making of orders which would go beyond the principles established by the decided cases.”

Florence Little got to keep the house and the chattels. For George Newell, given his disabilities and quality of life, his inheritance was raised to £3000. Another of the children, Florrie Platt, received just the £1000 inheritance, but with the notation that should her financial situation worsen, she could apply to the three charities named in the will for assistance. William Ralph’s inheritance was increased to £2000. Horace Newell admitted in his statement to the court that his father on visiting the family would give him money, from 5/- to £1. He ran a pharmacy at Opotiki at the time of his father’s death. Justice Callan decided that his inheritance didn’t need to be raised.

As for Lilly Newell, Justice Callan took into account that she already had a £3 per week income from the estate, plus assets worth more that £2000. The order raising George’s inheritance meant that he would be able to repay a debt to her, and she could realise her assets relatively easily. Like William, she had invested the £2000 he had given her in 1904 in property and mortgages in Palmerston North. She should therefore live in reasonable comfort from the income and realisation of her assets, with the open possibility that if her personal situation before her death required, she could apply for help from the three charities.

Florence Little owned 6 Oakley Avenue only until 1948, when she sold it. The house still exists.

Lilly Newell died in August 1958. She left £100 to the British and Foreign Bible Society, and the remainder to her four children equally, less £400 she had already given to William Ralph Newell in 1944.

From that point, William Newell’s estate was likely wound up, and the remaining proceeds finally distributed to the charities.

Sources:

Marriage registration and English census information from Ancestry.com

Marriage registration, Newell-Britland, NZ BDM

Evening Post, NZ Times, NZ Herald, Auckland Star, Manawatu Standard, Manawatu Times via Papers Past

Land information via Land Information New Zealand

Wills for William and Lilly Newell, Archives New Zealand and Family Search

Archives New Zealand files on the the court hearing: R25924723 & R25925014

Marriage registration and English census information from Ancestry.com

Marriage registration, Newell-Britland, NZ BDM

Evening Post, NZ Times, NZ Herald, Auckland Star, Manawatu Standard, Manawatu Times via Papers Past

Land information via Land Information New Zealand

Wills for William and Lilly Newell, Archives New Zealand and Family Search

Archives New Zealand files on the the court hearing: R25924723 & R25925014