The Avondale side of Te Kōtuitanga Olympic Park, briefly known as “Wolverton Park” during the 1970s bureaucratic stoush.

Google street view from Wolverton street, 2023

Background

The Whau River begins with two streams flowing together: Te Waitahurangi Avondale Stream from the Waitakere Ranges foothills to the west, and the Whau Stream from the deeply water-carved country of New Windsor, and the uplands in Mt Roskill between Richardson, Dominion Extension and White Swan Roads to the east. Where the streams meet is Te Kōtuitanga, the tip of land between the waters. For nearly 150 years of the post-Treaty of Waitangi era though, the approximate triangle between the Avondale and Whau streams and what is today Wolverton Street was mainly a wilderness of gorse, brush, wattle and not much else. Much of this, in the late 20th century, was dubbed Wolverton Park in the 1970s.

At least until around 1856 when the Great North Road through Avondale had been laid out, and likely the first Whau Bridge built alongside the present version, there was no formed crossing over either the Avondale or Whau streams. But on a map drawn up c.1850, a rather broad “Whau Bridge” was drawn, along with a curving line of road that would have linked the approximate line of Wolverton Street where it ended at the Whau Stream, with the approximate area of Clark Street. This idea may have between the reason behind the drafting of North Taylor Street and North Dilworth (later Ulster) Street through the area. Unlike the main part of Taylor Street and Ulster Road today – the parts of those roads north-west of Wolverton would remain unformed.

The Whau Townships North and South were surveyed in the 1850s, Whau Township North included Wolverton Park. Sales in both areas were less than successful for the Auckland Provincial Council, Whau North least of either. Lot 3 of that township (northern most part of the park) was set aside as a “Provincial reserve”. Below it, Lot 4 was a school reserve, as well as a triangle between the future “Ulster Road” and Wolverton Street, Lot 41, and Lot 9. Lots 5, 10 and 43 were set aside as religious reserves. Lots 5 and 10 however had a different fate.

Lot 42 was conveyed by Crown Grant to Bishop Augustus Selwyn in 1860, possibly with the idea of providing land for a church for the intended streamside village, but no one really knows for sure. In 1868, Selwyn placed it in trust with Sir William Martin, William Henry Kenny and George Patrick Pierce. All three men were long dead before the turn of the 20th century, but when the Anglican Diocese sought a title in 1940, their names remained, through to 1958. Beside Lot 42, Bishop Selwyn was also granted Lot 43 by Crown Grant in 1867. His name remained on the title through to 1955.

The school reserves Lots 4, 9 and 41 formally were conveyed to the Provincial Superintendent in 1861. These would remain so until 1878 when they were transferred to the Auckland School Commissioners, and then in 1910 back to the Crown as endowment land for primary school purposes, administered by the Lands Board.

The land history of the Avondale side of today’s “Olympic Park” is a complex one. Here, I’ve used a 1910 map to overlay the streets (Dilworth and Taylor above Wolverton only unformed paper roads), the site of the Auckland City Council depot (now the ambulance station and esplanade), the Anglican Diocesan land (church symbol), and the Crown land as at 1958.

The old Whau Township North was resurveyed in 1884, as the Crown tried again to attract interest from settlers. They were more successful this time, and the Land Board contemplated a new name for it. For a short while “Gordon” was considered, after General Charles George Gordon who had been killed earlier that year at Khartoum in the Sudan. But as there was already a Gordon Settlement elsewhere, the Land Board chose “Wolseley,” after another prominent general, Sir Garnet Wolseley, who had attempted to relieve Gordon. The road leading to the township was thus dubbed Wolseley Road (and another leading up the hill on the other side of Blockhouse Bay Road was named Garnet Road). In 1929, Bancroft Street was suggested by Auckland City Council as a new name for Wolseley Road, but three years later “Wolverton” was chosen. Dilworth Street (both north and south of Wolverton Street) was changed to Ulster Road in 1932 as well.

The Auckland City Council works depot

In 1872 Lots 1 and 2 of the Whau North Township, to the east of “Taylor Street,” were placed in the name of the Provincial Superintendent under the Public Reserves Act 1854, for educational purposes. This meant that funds from leasing the land were to be used to support the province’s schools. A few years after the Provincial Council ended, Henry James Bell and George Hemus of the Riversdale Tannery syndicate leased the two sections in 1883 for an unknown period, but not for long as the firm faded out from 1885. The wattles that were spread throughout the area and surrounds probably originated from the plantings undertaken by the firm while it was in operation. Bell & Gemmell had a lease for the land immediately on the other side of the Whau Stream (Allotment 101, 6 acres) from John Buchanan from 1879. This lease was transferred to Bell & Hemus in 1881, then to the Riversdale Manufacturing Company Ltd in 1882. The company bought Buchanan’s freehold in 1883, but it was subdivided, interests were sold, and the last shareholder sold up in 1893.

The land on the Wolverton Park side of the Whau Stream may have been used by the Avondale Borough Council as a rubbish tip during the 1920s, as there is a description of their tip being in Taylor Street, and affecting the Whau Stream, but this ceased in 1926 when the New Lynn Town Board complained. However, tipping at the site continued under the Auckland City Council. The “educational purposes” reservation on the site was revoked under the Lands Disposal Act 1942, and Lots 1 and 2 were vested in trust to the Auckland City Council, now set apart for “municipal purposes.” This was expanded by both the later closure of the unformed section of Taylor Street (Council had buildings on the paper road by 1961, obtaining clear title as a Local Purpose Reserve in 1981), and the purchase of part of the Anglican Diocese land on the other side of the road in 1965 for a hydatids testing strip. A 1980 aerial shows Council depot buildings already on site, including the closed part of Taylor Street.

In 1991 local residents campaigned for part of the Council works depot site to be turned into a reserve. This became the “Wolverton Esplanade” strip – but it still showed signs of being a tipping site: “small amounts of glass and metal are sticking out of the ground, with rubble and metal exposed on side slopes.” The Council proposed covering that over with 300mm of topsoil and clay. In 1993 the Auckland City Council land was divided into part leased for 30 years to St Johns Ambulance, and the Wolverton Esplanade along the foreshore.

The old Council depot, repurposed as an ambulance station. St John's have always called this "New Lynn" even though it clearly is on the Avondale side of the border. Probably they got confused with being west of the Whau Stream, when really New Lynn starts west of the Avondale Stream. All part of the confused site history here. Google street view, 2023.

The New Lynn Domain

Now directly administering the education reserves since the 1910 Act, the Commissioner of Crown Lands put those in the Wolverton Park area up for 21 year renewable leases in 1912. At least one part, Lot 5 at the northern-most point, was leased by 1917, but the lease was surrendered when the Crown land is in the process of being vested in the New Lynn Town Board.

New Lynn Town Board had started to make moves to have the Crown’s reserve land between the unformed part of Dilworth Street and the Avondale Stream vested in them as a recreation reserve and domain from 1916. They succeed in 1921 when the 4¼ acres was vested with the Town Board and became part of their New Lynn Domain on the other side (later known as Olympic Park). Then, for much of the next 45 years, the New Lynn Town Board and later Borough mainly forgot about the small Avondale part of their administrative area.

From SO 20070 (1918) LINZ records

Rupert Frederick Double of 26 Taylor Street leased the Avondale side of the New Lynn Domain from them for grazing in 1936. In return for a “peppercorn lease” Double offered to “fence, clear and grass” the area “for purpose of grazing cows.” He applied for a renewal of the lease in 1941, and asked for it to be extended to three years. In response, he was told he needed to comply with the terms of the lease, and completely clear the land of gorse, before a renewal could be considered. Double replied that through illness he’d had to dispose of stock, so was not able to carry out the terms of the lease. He advised he would be removing the fence.

The New Lynn Borough then advertised tenders for grazing there in 1942. Oddly, they didn’t seem to realise that they had control over all the land west of the domain’s part of Ulster Road up to the point, instead thinking that the former education reserves bookended their part. So, when they advertised the lease, they only referred to the middle portion.

The lessee was required to remove all noxious weeds and undergrowth in the first year, and only then might an extended three year lease be considered. The Borough retained the right at any time to enter the ground to plant trees. There is no information on the Borough’s file about any other leaseholders for the land than Double.

Prelude to the battle – the Lands Department’s subdivision idea

Things seem to have started to change for the Avondale side of the New Lynn Domain in 1958 when complaints were made about land that wasn’t actually part of it. There was a quarter-acre triangle of Crown Land that remained after roads, the domain ground and the Diocesan-owned land had been surveyed and disposed which had a 12 foot high gorse fire hazard problem. Auckland City Council found that this was an issue, and so served notice on the Department of Lands to fix the problem. This was sorted at that point by the Field Officer arranging with Crum Brick and Tile for the bulldozer they had working across the road to come over and sort out the gorse. The company quoted £12 to crush the gorse, and another £3 to heap it up and burn it. They went ahead and did the job.

The germ of an idea at the time from Lands Department perhaps to permanently sort the problem by subdividing and selling that quarter-acre was shot down by the City Council who said the subdivision should be for all the surrounding vacant land as well, even that owned by the Diocese.

So, in 1959, the gorse started to grow back. This time though, as the Diocese were spraying their own gorse, they were paid £10 to spray the Crown’s gorse as well.

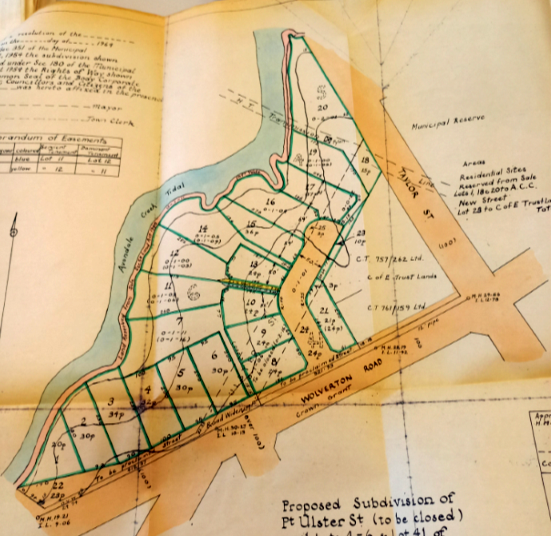

Come 1960, the Lands Department took up the idea of dealing with things once and for all. They prepared a subdivision plan proposal which included a part of the Diocesan land, as well as the adjoining Avondale part of the New Lynn Domain. The New Lynn Borough Council were approached to see if they were agreeable about releasing this back to the Crown for housing. Which they were, as they really didn’t know what to do with the Avondale side (they really had not spent any money on improvements there), and wanted to get the sale proceeds instead to improve their own part of the Domain. The plan included closing the unformed part of Ulster Road, forming a new cul-de-sac off Wolverton Street, and dividing the site into 20 sections. Lot 19, at the tip, was to be vested in Auckland City Council as a reserve and made part of a permanent metal dump site, along with the closed Taylor Street and a strip of the Diocesan land, which would take care of City Council demands for compensation for the closed Ulster Road. In exchange, the unformed part of Ulster Road would be added to the subdivision.

Wolverton Street was expected to become a secondary highway and widened 12 feet in the 1962-1967 period, so Lot 9 alongside the road was left off the subdivision plan. This also meant that if the plan was sorted and approved by the time the work on Wolverton Street was complete, it would make the actual work on the subdivision easier. There were those within the Department who backed an idea to have an industrial subdivision instead, rather than a residential one, but this went against City Council zoning, and the Council declined to change.

By 1962, the Lands Department expected to realize £14,000 from the sale of the land, of which £3,750 would be deducted and given to New Lynn Borough as their share. Information about this figure though was not given at the time to the Borough Council. £7440 was allowed as an estimate for Ministry of Works (MOW) expenditure in laying out the new road and underground utilities.

In 1965 Ministerial approval was formally received for revocation of domain status for the Avondale part of the domain, and for its subdivision for residential sites and ultimate disposal. So in 1966 the Avondale part of New Lynn Domain ceased to be a recreational reserve by gazette. It reverted back to the Crown.

In that year of 1966, it looked like the Lands Department could have gone ahead with their plans. All that was required was a change for the former domain ground to residential use under Auckland City’s operative Town Plan, and Avondale would have had a brand new subdivision there at the end of Wolverton Street.

But … Lands still couldn’t quite let go of the more lucrative idea of an industrial park. They kept asking the City Council, and the City Council kept on saying no (there was already the industrial development at the old

Glenburn brickyard site on St Georges Road, so they had no interest in another in the immediate area.)

So, by 1970, nothing had happened at the site. The MOW estimate had now risen (as at late 1969) to $16,500, covering section clearing, road formation, and installation of sanitary, stormwater and water mains. Some delay was due to MOW negotiations with Auckland City Council regarding certain works. By now, Lands Department were also considering provision of underground electricity reticulation as well, and a total of three out of the 20 residential sections in a revised subdivision were to be reserved for Auckland City Council municipal purposes – part of the now defunct Ulster Road (18), Lot 20 at the tip, and Lot 1 down near Wolverton Street.

Almost the fullest extent of the intended subdivision — the Church of England Trust Lands (Anglican Diocesan) would be added after this 1970 plan was drawn. Archives New Zealand file, R3950418

On top of this, they needed a new Ministerial approval for the increased costs, plus the amount of money to be paid to New Lynn also needed revision. As for the New Lynn Borough’s share of the proceeds, it was proposed by Lands Department that, once everything had been completed, they would seek an application from New Lynn Borough providing details of their development proposals. This would have been a ministerial refund, not a fixed set sum. Instead, the Director General decided to set a firm figure of $7,500 which was fairly well the same amount as from 1962 (the actual increased figure at the time, taking inflation into account, would have been nearly $11,000). Financial authority was duly granted for $19,780 for the subdivision costs, and the earthworks on the site went ahead.

But there was yet another delay. It wasn’t until late 1972 or early 1973 that Auckland City Council made the proposed rezoning public and open for submissions, and New Lynn Borough now objected. Yes, after agreeing happily to the idea of a residential subdivision on the former domain land in the 1960s, they’d had a change of mind in the 1970s. They were also listening to the concerns from their ratepayers. According to retired Police Chief-Inspector Henry Edwin Campin (1901-1985) who spoke at the Borough Council’s meeting on the subject “… until someone went mad with bulldozers there it was enjoyed by local children and residents … it had been covered with willows and wattles before it was bulldozed.” Campin was later reported as saying “We can’t just allow it to be taken. The western districts is starved of recreational land and we certainly can’t afford to lose what we have.”

In May the same year Rev Doug Kidd of St Judes Church in Avondale wrote to the MP for New Lynn, Jonathan Hunt (the start of a number of years Hunt would be involved with the Wolverton Park issue). In 1964 the Anglican Diocese had surveyed Lots 42 and 43 for subdivision. Three lots fronting Wolverton St are leased to Constance Costello March 1965 for 21 years, and these were leased in turn to contractors Michael and Kevin Patrick Sheehan in July that year. By 1971 the lessee of the Diocesan land had however abandoned the land and failed to pay any rent for years. A new lessee had been found who was prepared to pay for the land – but only if it was zoned industrial. The Lands Department and two other Wolverton Road landowners objected. Now, Kidd asked Hunt to let him know what the Crown intended to do, in order for the Diocese to apply for a rezoning of their land.

In July 1973, in response to New Lynn’s objection to the rezoning of the former Domain land from recreation reserve to residential, Lands considered a re-survey (again) to increase the area that would remain as a reserve alongside the Avondale Stream (originally limited to 10 feet wide, as they considered the stream would not be a recreation feature for the future residents.) The Department proposed to purchase the Diocesan land as well, and add that to their site – but while the Department was now dealing directly with the Diocesan office, Rev. Kidd kept on writing to Hunt, which sparked yet another ministerial inquiry seeking information from the Department, now to do with Rev Kidd’s suggestion of the Diocesan sites being used to provide housing for Pacific Island families. To that end, Rev Kidd also wrote to the Maori & Island Affairs Dept, claiming that “the Parochial District of Avondale” had the three sections. Which were all in the name, actually, of the General Trust Board of the Diocese of Auckland.

By October, Rev Kidd’s approaches to the Maori & Island Affairs Department had brought the negotiations Lands Department had been engaged in with the Diocese to purchase the land and add it to the subdivision to a screeching halt. Lands Department decided to just go ahead with the original subdivision, and leave Rev Kidd and the Diocese to their own negotiations regarding Pacific Island low cost housing on their land. The Maori & Island Affairs Department were still investigating, starting their own involved processes to determine whether the Diocesan land and Kidd’s proposal would suit their needs. They eventually said no.

In 1975, the Diocese offered to sell the Diocesan land to the Crown for $26,500. The Lands Department came to an agreement with the Maori & Pacific Island Department that several of the now 24 planned residential sections could be made available for Maori housing. The Land Settlement Board approved the purchase, which was made in May 1975.

The battle for Wolverton Park begins

The delays, though, were ultimately to prove fatal to the Lands Department plan for a residential subdivision at Wolverton Park. The delay in the 1960s while some in the Department refused to let go of the idea of an industrial site, and the bureaucratic jamming in the 1970s while the future of the Diocesan land was sorted out, meant that there had been time for the local community’s attitude toward the development to change, and for a new but very persistent opposition to appear. In September 1973 the Avondale-Waterview Ratepayers & Residents Association (AWRRA) was incorporated. The Society’s best-known member and Secretary, Kurt Brehmer, was to gain a local reputation for his persistence for local environmental causes for the rest of the century.

In AWRRA’s second year of incorporation, in June 1975, Auckland City Council advised Lands that (whoops), due to an oversight, they still hadn’t changed the zoning for the former domain from recreational to residential. They now started the public consultation process again. This was AWRRA’s opportunity. In October 1975, they lodged an objection to the Auckland City Council’s proposed zoning change from Recreation 1 to Residential 2 for the former domain land. The signatories to the formal objection were AWRRA Chairman J F J Clarke, and AWRRA Secretary Kurt Brehmer. Their grounds were: (1) there was a shortage of recreationally zoned land in Avondale, (2) the location adjacent to the Whau River made the land suitable for recreation, and (3) a recreation area would complement New Lynn’s Olympic Park. Clarke also went further, writing to both a New Lynn councillor, offering to have a meeting between the Borough Council and AWRRA, and also to Matiu Rata, then Minister of Lands, expressing the deep concerns of AWRRA. AWRRA were joined by first Avondale’s Community Committee, and soon after that of Blockhouse Bay, in opposing the proposed rezoning.

In November 1975, the Community Committee were advised by the Minister of Lands that joint discussions were taking place between the City Council, the Auckland Regional Authority, and the Lands Department “in regard to the future utilisation of the land concerned.” As a result, the reserve area beside the creek was enlarged, reducing the subdivision, but this still did not appease the protestors.

By January 1976, with the Housing Corporation slated to be the developers of the site, the City Council had received 10 objections to the zoning amendment. In September, the Land Settlement Board lodged a cross-objection, stating that the City Council didn’t have the legal authority to maintain the reserve designation unless they were prepared to purchase the land to retain it. They reminded the City Council that the underground services already installed were done so with their municipal consent. On 2 November, the City Council compromised, allowing all the objections and cross-objections in part. The land proposed to be rezoned was reduced, but that the rezoning would still proceed.

That year Auckland City Council obtained freehold title of the ends of the unformed Ulster Road as Allotments 81 and 84. The remaining cul-de-sac was later absorbed into the park in 2009.

The AWRRA were not about to give up. Having known Kurt Brehmer, I can personality attest to his tenacity, let alone that of his fellow campaigners. They appealed. In September 1977, the Town and Country Planning Appeal Board heard their appeal against the City Council’s decision, and stated that they would refuse it. However, they held off from officially deciding to refuse the appeal at that stage, though, because “two local committees” had not received a reply from the City Council regarding their suggestion the City Council buying the site to set up a swimming pool complex there. In April 1978, when the City Council still declined to purchase the site, the appeal was dismissed.

Still, AWRRA fought on. Now a “Wolverton Park Action Committee” was been formed, with Brehmer as their Secretary. They campaigned for all the land to be recreation reserve, with a swimming pool, skateboard park, adventure playground and picnic areas. In response to the appeal dismissal, the Action Committee launched two petitions, one of which to the City Council ultimately gained 3000 signatures.

Nevertheless, on 16 June 1978, the part of the domain land still required for the subdivision was duly rezoned as residential. All this had left the Crown with an 18-section subdivision, around half of the total original area, the rest potentially to be set aside as recreation reserve.

”After a lengthy and confused debate,” according to the NZ Herald on 30 June 1978, “the Auckland City Council last night again decided not to buy land in Wolverton Road, Avondale, for recreational use.” Councillor Jolyon Firth, a member of the Auckland Regional Authority as well, did not like the ARA getting involved, calling meetings with the Waitemata County, New Lynn Borough and Auckland City over the matter a case where the ARA, “lowered its standards and conduct to the level of a local pressure group.” The Mayor Sir Dove-Myer Robinson, “said he would strongly protest to the ARA for poking its nose into a local issue.”

In 1981, after another grinding series of objections, appeals and dismissal of appeals, resulting in an even larger area now set aside as foreshore reserve, there was a new Crown proposal simply to transfer the remainder to Housing Corporation in return for $60,000. Housing Corporation in turn expressed interest in transferring a large part of this to a private development company for a 40-bed resthome.

Continuing their changed public attitude, the New Lynn Borough Council in 1982 were “convinced that the development of Wolverton Park as a recreation reserve is an inevitable and necessary adjunct to its own reserve, an essential solution to the demands for recreational facilities in the surrounding area.” They entered into talks along these lines with the Auckland City Council. Yet in a case of mixed messages via a phone call to the City Council’s planning division in August that year, New Lynn’s borough engineer, Garth Freeman, was reported as saying that “he was satisfied that the land area presently available to Olympic Park is sufficient” to meet both present and future recreational needs in the locality.

By September 1983 though, worn down after eight years of hearings and appeals and petitions, the Lands Department had had enough. They asked New Lynn Borough if they were interested in acquiring the land. By 1985, the answer came back – yes. Four years later New Lynn Borough agreed to pay the Crown $80,000 for the former New Lynn Domain land (Lot 88), the vestige triangle of land (Lot 86) and the remainder of the former Diocesan land (Lot 87), leaving only the paper cul-de-sac (sorted this century). Waitakere City Council as the territorial authority after the 1989 amalgamations finally obtained title, as a recreation reserve, in 1999. More land was gifted, for a token $1, by Auckland City to Waitakere to increase the size of the Avondale part of the now enlarged Olympic Park, and by 2007 the enlarged park was completed.

To this day, part of the paper Taylor Street still has no title attached to it, but is part of the park, just down from the northern-most point. Someone may sort that out, if they need to, in the future.

Otherwise – perhaps best to just leave things be. Apart from reinstating the name Te Kōtuitanga to the park.

%20WA-10778-G.JPG)