A young immigrant, having served his country during World War II, travelled to New Zealand for a new life. Here, he found love, but he also met his death far too soon in a New Windsor boarding house.

The boarding house was at what was then 5 Batkin Road, today’s 39 Batkin, the site of the now strangely named Blockhouse Bay Rest Home and Hospital (not in Blockhouse Bay, and perhaps only barely within sight of the suburb or the bay). The site was the property of members of the Moros family from 1905 through to 1967, starting out as part of one of the farms which made up the early suburb of New Windsor.

The story begins with Nicholas George Moros (c.1855-1908), a fisherman from the Greek island of Syros, who somehow ended up in Wales in the early 1870s. There, he married a young widow named Eliza, who already had a son by her first marriage (her husband appears to have been lost at sea). Nicholas and Eliza would go on to have at least seven more children of their own.

The Moros family emigrated to New Zealand in 1886 aboard the Arawa. Here, Nicholas worked as a fisherman in Dargaville and applied for naturalisation as a British citizen in 1888. Over time in the township he acquired a fruit and fish shop, an attached billiard saloon, as well as the family’s house all on Victoria Street. A fire in 1900 wiped out Moros’ buildings; Moros bought a number of marble ornaments in Auckland and tried asking permission from the authorities to hold an Art Union raffle to recoup his losses, but was turned down. To an extent, Moros did rebuild his business in Dargaville after all, but the family soon decided to move on.

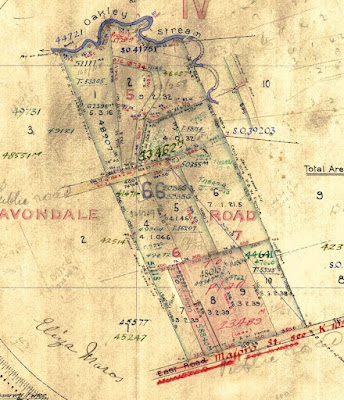

In 1905, Moros (under Eliza’s name) bought 20 acres in New Windsor between the end of Batkin Road and Te Auaunga Oakley Creek from the Batkin family. The Moroses bought another nearly 31 acres immediately adjoining, stretching to present day Maioro Street from two businessmen who, only two months before, had purchased the land also from the Batkins. The house at 5 (39) Batkin Road may well have been the original Batkin homestead from around 1899. This six-roomed house would become the Moros family home, and would remain in their ownership through to 1967, although there was in 1908 another 19th century six-roomed house on the former Victor Longuet vineyard and orchard property closer to Oakley Creek.

Nicholas Moros put all 50 acres of the New Windsor property up for sale in February 1908, including both houses, as “2 First-Class Fruit and Poultry Farms,” the northern 20 acres with 150 fruit trees, “3 acres ploughed and well manured with fish offal,” four large iron tanks and “a splendid well of water.” The main Batkin 30 acres to the south was: “First-Class blue clay land”, subdivided into three fields with stable, three loose-boxes, two fowlhouses, a dairy, cowshed (six bails, concrete floor), piggery and other features. There were no sales, however, and Nicholas Moros died in October 1908, just eight months later, still with two outstanding mortgages on the property, leaving behind his widow Eliza with the relatively large farm in rural New Windsor and teenage children still to look after.

Eliza Moros though set-to and proceed to start selling the property off from 1910. By 1922, all that remained was the four and a quarter acre section which included the house at 5 (39) Batkin Road, plus part of the future road beside.

On 15 November 1915 her daughter Despineo, then known more often as Spineo for short, married Charles Edward Henry Brothers at Avondale’s St Judes Anglican Church, the service officiated by Rev Harold Robertson Jecks. The couple moved to Frankton Junction near Hamilton during the remainder of the First World War, Charles Brothers working a railway employee, but they had shifted back to Auckland by the late 1920s. In 1935, the couple separated, and Charles shifted to Tauranga. Two years later, on hearing word about her husband, Spineo went there and found him living with another woman who styled herself as “Mrs Brothers.” In 1939, Spineo was granted a divorce.

Eliza Moros died at the Batkin Road house in 1940 at the age of 90, survived by three sons and three daughters. A year before her death, Eliza lost her sight completely. Up to that point, according to her obituary, she loved going to see picture shows, and had a keen memory.

In 1944 the estate’s executors transferred title of the house to Spineo, who had been living at the house with her mother and brother, John Nicholas Moros, since 1935. At least from the mid 1940s, Spineo started expanding the premises, adding rooms and out-buildings until it became a full-fledged boarding house, capable of accommodating around 16 lodgers. Many of these were single men or even couples with small children working at the nearby gardens, such as the large one run by Arthur Currey on New Windsor Road, or the brickyards at St Georges Road, and the Amalgamated Brick and Pipe works further west at New Lynn, along with the Ambrico (soon to be known as Crown Lynn) pottery.

One of those lodgers was Gordon James Pepper.

Pepper was born 19 July 1926 at Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire in England, the only son of Arthur Leonard Pepper and his wife Mary Ellen. Gordon was apprenticed as a mould-maker in a pottery factory in his home town at the age of 14, working there until he volunteered for war service at 18. He served with the Warwickshire Regiment for 12 months, and was then transferred to the Royal Pioneer Corps, going to France on D-Day plus 4, then Germany, rising to the rank of Quarter-Master Sergeant before returning to England to be demobilised in 1947.

Pepper returned to the pottery works, and toward the end of 1948 he received an offer of work from the other side of the world, at Crown Lynn pottery. So, he packed up, said goodbye once again to his home, and arrived at Wellington on 13 January, aboard the Atlantis. Two days after that, he was in Auckland, secured his job as a mould maker at the New Lynn pottery, and took up lodgings at Batkin Road.

In July, Pepper got engaged to Edna Coward, who happened to be a friend of Spineo Brothers’ family, with the marriage set to take place towards the end of that year. Pepper wanted to be able to buy a house for himself and his bride-to-be, so decided to take out a life insurance policy on himself as a form of security. On 1 October 1949, he woke up at Batkin Road at 3.30 am to start work at 4 am. After his shift, he headed by car into the city for the necessary medical examination, arriving at the doctor’s offices at 9.45 am, running up two flights of stairs because he was slightly late. The doctor found him to be in perfect health. Pepper was back at Batkin Road by around 11 am, did some washing, and had lunch at 1.15 pm, before retiring to his bedroom, which he shared with fellow Tunstall native Vincent Stevenson (another who worked at Crown Lynn), for a nap. He had tickets for a showing at one of the picture theatres for himself and Edna later that evening, so intended just to have a rest break in the course of a busy day.

Around 5.30 pm, Pepper came into the kitchen, dressed in pyjamas and trousers, apparently with a bit of upset in his stomach. Up to that point, he’d had nothing out of the ordinary to eat – his lunch earlier that afternoon was fried bacon and cheese. He asked Mrs Brothers if he could have some of her Andrews Liver Salts. She told him that the salts had perished, and instead to use a bottle of Enos fruit salts from the kitchen’s medicine cupboard instead. The bottle was still store-wrapped and seemingly unopened. Pepper took off the wrapper, poured some of the salts into a teaspoon, then mixed them in a cup of water, before drinking.

His immediate reaction to Brothers was, “I don’t like your Enos Fruit Salts, they taste bitter.” Brothers dismissed his remark, telling him he was just being “faddy.” Pepper asked another boarder standing nearby, Gordon Wood, to take a taste. Wood dipped a finger into the cup, and also remarked on the bitterness.

Whether Pepper finished the cup of water isn’t known. It was later found to have been washed and put away. The bottle of fruit salts was returned to the cabinet.

Pepper then went outside, brought his washing in from the line, and Brothers put his washing in the hot press to air off. A little later, about to start ironing his shirt for his evening with Edna, Pepper suddenly told Brothers, “I feel funny, I feel giddy.” Brothers couldn’t see that he looked unwell, but told him to go lie down for a bit. Pepper refused, continued ironing, then complained that his legs had gone stiff. A moment later, he told Brothers he couldn’t walk.

She helped him back to his room, took off his slippers for him and laid him on the bed, covering him with the bed clothes, helped by Stevenson. Pepper asked if it had been the fruit salts that had affected him. Around 6 pm, Brothers rang Dr William Gordon Davidson who was living at 1834 Great North Road in Avondale. She reported that Pepper had felt unwell after taking the fruit salts, and asked Dr Davidson if that might be the cause. The doctor said no, “there was nothing in fruit salts to cause any harm,” and it was more likely just a case of influenza. He told her to give Pepper aspirins and lemon juice. Dr Davidson and his wife were, at the time, in the process of dressing for a social evening at the home of Dr Robert Warnock in Pt Chevalier.

Brothers had no chance of giving Pepper any aspirin or lemon juice. His condition worsened, and he began to complain about the light. She tried contacting another doctor, in vain, then rang Dr. Davidson again at around 7.20 pm.

Dr Davidson later testified: “Just as we were leaving the house between 7.20 pm and 7.25 pm, Mrs Brothers telephoned again. She said, ‘That he was much worse and that his legs appeared to be stiff.’ I told her that I didn’t think much of this and that the aspirin had hardly had time to work. She then said that ‘She didn’t think it was the flu.’ I told her that I still thought it was the flu and to carry on with the treatment. I told her that I was going out for the evening and would be home about 11 pm, and if he was any worse then to give me a ring and I would come up and see him. She agreed to this.”

By now, Pepper was convulsing and crying out in pain. Brothers tried called Dr Davidson again ten minutes later, but by then he had left his house, and all Brothers could do was leave a message. This was passed on by phone to Dr Warnock, who greeted Dr and Mrs Davidson at his door when they arrived with the news that something was very wrong at Batkin Road.

When Brothers put down the phone, she returned to Pepper’s room – to find that her lodger had passed away.

Doctor Davidson finally arrived at 7.55 pm, and later stated that he was “shocked” to find Pepper dead, his face “abnormally pale.” He thought at the time that perhaps Pepper had suffered a brain haemorrhage. When he called the police, however, he wisely told them about the fruit salts. After the local constable arrived, the doctor pointed out the bottle of fruit salts to him, then left Batkin Road to return to Dr Warnock’s house. A little later, a police sergeant went to Pt Chevalier, asking both Drs Warnock and Davidson their opinion about the fruit salts bottle. Both declared the taste bitter, and Dr Davidson later stated that he’d noticed “some needle shaped shiny crystals in the bottle which did not seem usual for fruit salts”.

This turned out to be crystals of strychnine hydrochloride, spread almost throughout the bottle in six distinct layers, each layer (apart from the untampered one right at the bottom) was laced with varying amounts of the poison. The analysis found that the bottle had been opened, most of the contents mixed with the strychnine crystals, before the fruit salts were then carefully poured back into the bottle, and the whole resealed as if there was nothing wrong.

There is no indication that Gordon Pepper was the intended victim. Anyone in the boarding house could have felt some indigestion over the period the bottle was in the household. It appears that, like a roll of the dice, Pepper was simply unfortunate that day.

So – how did the bottle get into Spineo Brothers’ boarding house?

Spineo’s brother John Nicholas Moros worked as a fishcurer and later general labourer, and had lived in the family home at Batkin Road since the First World War. At the time of Pepper’s death, Moros said that he assisted his sister with odd jobs around the place. He recalled that, months before Pepper’s death, he went outside for a smoke, and walked around the house to check to see if that day’s copy of the Auckland Star had been tossed, as usual, over the front hedge onto their lawn. There was no newspaper, but instead he found a wrapped parcel on the front lawn, six yards from the road and six to eight feet from the path going around the right side of the house. The parcel was wrapped in brown paper and tied with white string, “as if it had just come out of a shop,” Moros later testified. There was no writing on it at all, and was completely dry.

Moros took it inside and showed his sister. He opened it, to find that it contained “two cakes of washing soap, a long stick of shaving soap, one packet of Gillette razor blades” – and a bottle wrapped in paper, the Enos fruit salts. Brothers added in her testimony that the bottle “was wrapped in its original wrapper,” including corrugated cardboard. She stated that Moros had found the parcel “four to six months” before Pepper’s death. Brothers wondered if the parcel had been dropped by one of the lodgers, so left it in the kitchen for some time. When no one asked for it, she put the fruit salts bottle in the medicine cabinet. Brothers claimed she never bought Enos fruit salts, and she was certain that the bottle that had been laced with strychnine was the one from the mysterious parcel her brother found on the front lawn.

The coroner Alfred Addison’s finding after the hearing in March 1950 reads thus: “… the said Gordon James Pepper died on the 1st day of October 1949 at 5 Batkin Road Avondale Auckland and that the cause of his death was strychnine poisoning as the result of taking a dose of fruit salts with which had been mixed by some (as yet unknown) person with murderous intent needle crystals of strychnine hydrochloride.” Addison was reported in the newspapers as continuing: “Pepper was the victim of one of the foulest murders in this country’s history. Police inquiries are not concluded in this case.”

However, to date, the poisoner’s identity or motive remains unknown.

Gordon Pepper was laid to rest at Waikumete Cemetery with a military headstone. A memorial service was held for him back at Stoke-on-Trent in October 1949, and his widowed mother received the proceeds of his estate, totalling £335 8s. The Daily Mirror referred to the case as “The Health Salts Murder.”

John Moros who had found the fatal parcel, died in 1958 at the age of 73.

Spineo Brothers continued running the boarding house through the 1950s, and possibly into the 1960s as well. She subdivided and sold most of the rear section to Kingram Estates Ltd in 1961, and Brothers Street was laid out, named after her. In 1967, the remainder, including the sprawl of buildings that made up her boarding house, was sold in 1967, and became the Bettina Rest Home, today site of the Blockhouse Bay Rest Home and Hospital. Spineo died in 1981, and shares a plot at Waikumete Cemetery with her brother John, next to their mother and father.

Her son Raymond Nicholas Brothers (1924-1988) who had lived for a time with his mother at Batkin Road while a student, went on to a career as a noted lecturer, professor and geologist attached with the Department of Geology at the University of Auckland from 1951, and Head of Department from 1972 to 1980. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1975.

So, as you head down Batkin Road, to drive along Brothers Street to get to Valonia Street, spare a thought for the Moros-Brothers family. But especially remember Gordon Pepper, a young immigrant keen to make a home and living for himself and his bride-to-be in a new country after a dreadful war. Someone who may have become part of the history of Crown Lynn with his skills had he lived. Instead only to perish horribly due to someone’s callous decision to do harm. The product of that decision wrapped in a parcel tied with string, left one day on a front lawn in Batkin Road.

Images: Advertisement from Northern Advocate, 22 January 1935; detail from DP 4801, LINZ records.