Spring racing at Avondale, from Auckland Weekly News 27 September 1923, AWNS-19230927-47-1,

Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections

(Following on from part one)

For a number of years in the 1920s, it seemed that the Avondale Jockey Club committee members had to constantly watch their backs, taking a group deep breath whenever opening the morning paper, in case something else had cropped up to try to end their endeavour. Having seen off the earlier threat of closure in 1922, it may have freshly rattled their nerves when it was reported early in 1925 that former Avondale resident Richard Francis Bollard, then Minister of Internal Affairs and son of first AJC president John Bollard, spoke of amalgamating Avondale with Ellerslie’s Auckland Racing Club. Bollard though later emphatically denied that such was the case. The coal gas explosion which wrecked part of the club’s totalisator house in October 1924 probably added to the tensions at the time.

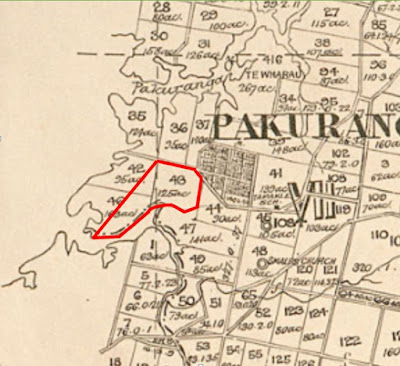

But the club had their plans, and they had a firm business basis with which to do them. The annual report dated 10 July 1923 proclaimed, in bold letters, that “the Club has no liabilities whatever.” During 1924, they purchased land between the course and Wingate Street; the land once leased from Moss Davis and the Hancock Brewery to the east, including the strip fronting onto Great North Road, Webb’s Paddock in the middle, and the western end from Ellen Barker. More of the former Bollard farm was purchased along Ash Street, the site today of Sandy and Nacton Lanes. The club’s fullest extent would be reached, as mentioned in the previous article, in 1943 with the resumption of Jane Bollard’s property on Rosebank Road, but – by 1925, most of what those living in Avondale from the mid-20th century onward recognised as part of Avondale’s recreational greenspace was together under the club’s ownership.

The buildings

The layout of the main structures for the course had always reflected the divide between members of the club, afforded due privileges of that membership, and the general public. While situated at the Wingate Street side of the course, this divide was probably not so pronounced, due to space restrictions. But once the shift had taken place to the Ash Street side, onto Bollard’s former land, the spacing of the demarcated areas laid out in 1900-1901 remained at least to the mid 1980s.

Closest to the Whau River was the public area. This was fenced off from the main area beside it, and it was where the old 1890s grandstand that had been shifted across was placed. At some point between around 1905 and the late 1920s this oldest part of the racecourse architecture was removed. Plans were drawn up for open terraced seating in its place in 1928. The new stand was roofed in 1937. This was known as both the “public stand” and the “Derby Stand” at various times. It was destroyed by fire in 1985.

Next to the public area was the lawn enclosure, featuring the main grandstand, the 1900-1901 version designed by Edward Bartley, with its distinctive “jockey’s cap” roof shape. It was shifted forward, closer to the track, in 1936, and had concrete terraces added to it. From 1963 it lost its prominence due to the construction of a new main and larger grandstand immediately adjoining it.

The grand totalisator building from 1911 crossed the division between the public area and the lawn enclosure, and was divided off as well to reflect the separation of facilities between the two enclosures, which of course cost different admission fees as well. In September 1939 it cost 1-/ to enter the racecourse at the public enclosure, and another 1/- to park your car there as well. Entrance to the lawn enclosure (which included the general admittance) was 6/- for gentlemen, 8-/ for ladies, and all vehicles 2/6. Children under 12 were not permitted to the Grandstand Enclosure. “Men in uniform of His Majesty’s Forces will be admitted free.”

The layout takes shape

The greatest change was in the racetrack layout. Plans were drawn up in late 1925 for the old course to be completely obliterated, with a back straight now running nearly the full length of Wingate Street down to and including part of the old brickyard land. Alongside this, lasting until the 1990s, a steeplechase route was also added. The track was effectively shifted south as well as widened, leaving the members and public stands a considerable distance back from the track (a reason why both stands were eventually shifted forward, and the members stand realigned at an angle, to get the best views). H Bray & Co of Onehunga were the successful tenderers, and by February 1926 Avondale residents witnessed huge ploughs drawn by teams of ten and twelve horses engaged in the work of shifting topsoil and laying the foundation layers for the new track. Work was completed by February 1928. This didn’t include the mile/1600 metre start which was laid out in 1939, up by Great North Road and behind the block of shops there (as at July 2019, the site of the proposed new community centre and library), or the half-mile/800 metre start laid out in the 1950s at the Whau Creek end.

Unfortunately, 1928 marked the end of the club’s nearly three decade long working association with architect Norman Wade, carrying on from the earlier plans drawn up in the 1890s for various structures by Edward Bartley. A legal disagreement over professional costs for the shifting and rebuilding of the grandstand resulted in a parting of the ways between the architect and the club.

Possibly, the oncoming Great Depression was the brake to any further work developing the racecourse facilities until halfway through the following decade anyway. As mentioned before, the work of shifting the members stand and the public stand took place in 1936, the public stand cut in half to complete the task. Ornate gates were added to the Elm Street entrance in 1937. In 1939, while totalisator earnings appeared to be lower than they were in 1928 for various reasons, it was still reported that the club looked forward to a brilliant 1940 season, with their racecourse facilities finally all in place, the new mile start in use, along with a training track in the infield.

But then, of course, along came World War II.

The racecourse during the war

Up until July 1941, military camps on the racecourse were of a temporary nature, not really impacting on the club’s operations. But that July, construction began for a permanent camp, meaning that Avondale’s meetings migrated to Ellerslie for the duration. This was something that hadn’t happened before on the course – roads were laid down, rows of huts installed and erected. During the course of the camp’s existence, it was divided into army and naval transit camps, and even a POW camp for a time, after the uprising of Japanese prisoners at Featherston in 1943. There was also a temporary US Forces camp for a month only.

From January 1944, the military camp was converted by the government into a Works Department camp. The Army vacated the racecourse in July 1945, and the Public Works Department finally evacuated in February 1947. The Jockey Club put in a £15,422 claim for compensation. They eventually agreed to accept £6000 cash plus some buildings (two mess halls, a recreation hall, and a cottage at the back of the tote building), and repairs to fences, latrines, stables, horse stalls, tote building, turnstiles and ticket boxes, outside stand, lawn grandstand, judges box, jockey’s board, steward’s stand and casualty room totalling £7500. The claim was eventually split between PWD and the Army. The club initially intended using at least one hut as a restaurant, but by March 1947 had submitted plans to the City Council for joining together and converting three ex-Army huts into an afternoon tearoom just in behind the public stand, along with a separate soft-drink stand using another ex-Army building just to the west.

The City Council recreation areas

On 5 October 1944, City Councillor Archibald Ewing Brownlie set in motion the process by which the Avondale community and surrounding districts came to be able to enjoy using large parts of the racecourse land on a long-term and permanent basis for recreation. At the time, the racecourse was still under government occupation. A full return to normal operations was nearly three years away. Brownlie asked the Parks Committee to look into the possibility of securing land at the racecourse for public use, without interfering with the racing and training there. The committee headed out to visit the course the following month, and by 8 December provided a report describing what was proposed to be acquired from the jockey club.

The area beside the mile start was on the December 1944 list, with the exception of the Great North Road frontage to a depth of around 100 feet, so the club could have the option at a later point of subdividing and selling that part for commercial retail use as part of the shopping centre. That subdivision came about in 1961, with sales taking place from that point. (As at July 2019, this is the proposed site for Avondale’s new Community Centre and Library). The area ultimately vested as a gift to the City Council in 1959 curved around to have a Racecourse Parade frontage. Tennis courts were set up here, later becoming netball courts under the administration of Western Districts Netball Association during the 1970s.

The other main area was around 19 acres at the western end of the racecourse, fronting the Whau Creek. Today, this is the residential area of Corregidor and Michael Foley Place, the Rizal Reserve, and the site sold in 2017 for the Tamora Lane development. Back in the 1940s, it was an area of broken ground, topsoil stripped off (possibly transferred to the main part of the racecourse during the work in the late 1920s), littered with remains from the earlier brickmaking operations there plus the club’s own rubbish tipping. Two power pylons were already in place on the site, but the City Engineer still remained keen, suggesting that part of the waterway could be reclaimed to provide more space for the required playing fields. In a lengthy report from February 1945, the City Engineer went on to speculate that acquiring the whole of the racecourse’s 124 acres would go a long way toward the calculated 210 acres required to provide for the expected future recreational needs of not only Avondale but the wider district, creating a regional reserve.

“At the present time,” he wrote, in what would now appear to be a rather prophetic piece of report writing, “under the present conditions of Metropolitan Government, to acquire such a total area for regional purposes would be beyond reasonable expectation. It is possible that at some future time, the area might be considered for subdivision for urban development. In that event a portion at least will no doubt be acquired for reserve and in any case the opportunity would present itself for acquiring the whole area. Circumstances may then be different.”

The report was adopted by the Council in March 1945. By the end of April, the jockey club put forward a further proposal: that the city council lease, for a term of 25 years, the infield area bounded by the training tracks for 1/- per annum. In March 1947, the Avondale branch of Citizens & Ratepayers convened a meeting at Avondale College, which came up with the suggestion that twelve playing fields in the area to be leased by the council be made up of: Rugby and League, seven fields; Soccer, two fields; and Hockey, three fields. Two concrete cricket pitches were also recommended. In June, the council authorised the laying out of ten playing fields in the inner part of the racecourse. There was a delay regarding the setting up of the playing fields, as the Auckland Rugby Union was using that space at the time, and asked to be able to see the winter season out. Drawn up in 1947 as part of the wider agreement covering that, plus the two outright gifts of land, the lease between the Jockey Club and the City Council was eventually agreed to and signed in 1952.

As for the 19 acres by the river – some members of the Jockey Club committee had a change of heart by March 1948. They felt that “a mistake had been made as they thought that the area would be required for future extension [the 800 metre start] and the siting of racing stables.” The Council’s Town Planning officer assured them that there was provision in the agreement for the club to have land handed back to provide for the additional starting space, but the committee members were adamant. The gifting of that part of the racecourse land to the council was, from that point on, off the table.

The lease for the inner field playing areas expired in 1977 without right of renewal. The Jockey Club required, as part of the agreement to renew the lease, the provision of a hard-surface car parking area at the north-eastern end, and underground toilets in the midfield. The council’s Department of Works designed the required toilets, male and female, in 1978, and these were built for around $28,000. The matter of the hard-surface carpark however dragged on, and the lease wasn’t formally renewed at that time, although the club and the council came to an agreement that use could continue while negotiations carried on.

In July 1981, Councillor Jolyon Firth described the toilets in a memo to the chairman of the Parks Committee as:

“... a four-holer semi-submerged Clochemerle sited in majestic isolation in the mid-field area of the racecourse. This was considered necessary as, in want of such a facility, many people had no alternative but to make a convenience of the back of the Club’s dividend indicator board thus causing discolouration and rot to a most important raceday facility.

“In constructing this new facility, the Council was obviously mindful of the dictum of the late Chic Sale, author of The Specialist who, in his ground rules for these types of facilities, made famous the words “For every Palace a privy, and every privy a Palace” … There was no official opening. Such an event would have been embarrassing because no sooner had the edifice been put in place, then it flooded. A member of the Suburbs Rugby Club told me that it was “awash to the gunwhales.” Having got past that calamity the facility is now a great convenience for thousands of people. And, of course, the Club’s dividend indicator board is no longer rotting away …”

The facilities into the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s

After the five year gap, the Avondale Jockey Club’s return to racing at Avondale after the war did not go as smoothly as planned. Their spring meeting that year was to be their first, but before it took place, major repairs and maintenance were required to the buildings due to the military occupation. Although the government promised to undertake these repairs, these were deemed by the Auckland Carpenters and Labourers Unions to not be “essential” work, and the job was declared black. Presumably, some sort of compromise was reached between the government, the contractors and the unions, for in September 1946 the first post-war race meeting was held on the course.

The racecourse’s 1950s story is told mainly in the developments made to the course and its facilities. The additional 800 metre start was added at the Whau Creek end. An addition was built for doubles betting at the auxiliary tote building at the rear of the lawn enclosure by 1951, along with a standalone indicator board, and an eastern addition to the members grandstand. Five small open public stands were built beside the old 1900 grandstand around 1951.

An amendment to the Liquor Licensing Act was passed in 1960, and this allowed the club to once again sell alcohol from 1961, even though Avondale itself remained dry. The club replaced the old huts that had served as tearooms with a beer garden, and constructed a members bar and a garden bar attached to the outer public stand. Around this time, the old 1911 tote building was converted into a cafeteria. Liquor sales allowed the club to go ahead with the new public stand next to and overshadowing the old 1900 version, replacing the small 1950s open stands. The cost of the grandstand project at the time was £140,000, and it opened in January 1963. In behind the old stand, the club provided asphalt basketball courts for the use of 11 Western District schools from May 1964 until the old stand was also later replaced.

The club raced for only six days a year (raised to eight by 1969), but had the third highest daily totalisator turnover in the country. It maintained three training areas beside the main track: the plough, the two-year-old and the No. 1 grass. The club’s success during this period shows in the further developments of a new members stand in 1964, and the installation of an infield indicator in 1967. A block of 18 loose boxes were built beside the Whau River in 1969.

Divots kicked up by horses on raceday however still took him and 21 helpers several hours to replace the following day, on top of the cleaning of the 146 lavatories dotted around the course.

In 1976-1977, the old grandstand from 1900 with the “jockey cap” roof, was finally demolished for another public grandstand between the 1963 building and the members stand. A birdcage track was added in front of the members stand in 1979. A new tote building was constructed in 1983 for the introduction of the new Jetbet system where the same window could be used to place bets, as well as collect the dividends. A new parade ring was installed in 1984.

The racecourse hosted the New Zealand Polynesian festival over the course of three days in February 1981, an event started in the early 1970s to encourage competitions among Maori cultural groups, known today as Te Matatini.

In 1985, fire ripped through the 1928-1937 outer or Derby grandstand, and the remains were demolished, not to be replaced. Reports at the time erroneously described it as part of the old racecourse from the 1890s. In fact, the oldest structure of all, what remained of the 1911 tote building, continued on for another few years, finally disappearing when the course was later subdivided in the early 1990s.

The Avondale Sunday Market

The market originated as an idea for a method of fundraising used by the West Auckland Labour Party electorate committees. The Otara flea market had started for partly the same reasons, back in the late 1970s. In the early 1980s, flea markets were held by schools, and also by Suburbs Rugby Football Club in Avondale on Saturdays from 1978 – it doesn’t seem to have been all that much of a stretch to take the idea, once a rental agreement was arranged with the Jockey Club, to establish a regular event each week on the outer grounds, accessed from Ash Street.

From 1983 to at least 1991, the market appears to have been run by a committee of trustees on behalf of the electorate committees. A minute book exists for that time period, but my information here comes mainly from the newspapers and the council’s property file on the racecourse.

The trustees approached the City Council on the matter in May 1982, calling it the “West Auckland Market Day”, and an application to operate the flea market was lodged with the Council in July. This was granted in October that year for a period of six months before reassessment, with the conditions that the market operated only from 9am to 12 midday, with no stalls to be set up prior to 8am. Only second hand goods could be sold there. At the time, the principal planner reporting back to his department didn’t feel that the market, selling only second hand goods, would prove to be much in the way of competition for the retailers in the Avondale Shopping Centre area, and “moreover, the scale of traffic that would be generated on Sunday by the fleamarket would be considerably lower than that generated by Racecourse activities during the other days of the week … Avondale Racecourse, with its large area of open space, carparking and public facilities appears well suited to a fleamarket.”

A later report stated that the first such market opened at the racecourse in November 1982, a month after the approval was given, and there are letters in Council files from January 1983 referring to traffic issues on Sundays in the Ash Street area, seeming to involve the market. But there was no mention made in the Western Leader in November 1982 – the earliest notice advising that stall holders could contact the organisers actually appearing in the newspaper on 22 February 1983.

In July 1983, a further three months was granted to the organisers by the Council. In 1984, an application was lodged with Council to allow the market to operate on a permanent basis, but the system remained of six-monthly approvals, on the basis of regular review.

The market proved exceedingly popular, and despite the initial small scale continued to grow. By the week preceding Christmas 1984, 206 stalls were operating. By February 1985, rather than just “second hand goods”, the market had attained a similar flavour to that of today, selling fresh produce, meat, fish and shellfish, flowers and plants, homebaked goods, takeaways, new clothing and footwear, second hand clothing and footwear, craftwork, and “second-hand household effects.” Gates were opened to the public at 8 am. It rarely ran much over the 12 midday time limit, as most of the vendors had already sold out and gone home before then.

Permanent consent to operate the market was granted in 1989, with a variation of conditions in 1995, after the market appears to have ceased being controlled by community trustees and became a private business.

Permanent consent to operate the market was granted in 1989, with a variation of conditions in 1995, after the market appears to have ceased being controlled by community trustees and became a private business.

Brand new ideas for the 1980s – night racing at Avondale

According to George Boyle’s Highlights from One Hundred Years of Racing at Avondale Jockey Club (1990), it was outgoing Club President Peter Masters who suggested in October 1983 that consideration should be given to night racing, as well as meetings on Sundays, “to bring New Zealand racing out of the Victorian age.” His cue was taken up by club secretary John Wild, credited by Boyle as being the driving force behind the project to introduce night thoroughbred racing to Auckland. He and Don Marshall travelled to Hong Kong and West Germany to view other facilities, and checked out manufacturers of the required lighting systems.

By October 1984 the project’s cost had risen from $2 million to $3 million. A request for a loan of $1 million from the Racing Authority was turned down. Nonetheless, the club plugged on, raised finance, sought and gained Council approval for the installation of the lights, and in October 1985 at that year’s AGM announced the appointment of Lobley, Treidel and Davies of Melbourne as the consulting engineers for the work. The first contract was let by June 1986, and the first of the lighting masts was in the ground by November that year.

The club held a dress rehearsal on 9 March 1987, a trials meeting with no betting, but an estimated 3000 turned up anyway for the spectacle. The date of the first main meeting with full betting was, perhaps rather unfortunately in the light of what happened so soon afterward, April Fools Day 1987. Nevertheless, the official attendance figure was a crowd of 9380. The night was deemed a success, but John Wild shared in that success for only just over a week before he died from a heart attack.

When things came unstuck – the beginning of the land sales

In October 1987 came the sharemarket crash. The economy went into downturn, and financial markets were hard hit. General betting turnover went down as well. Some blamed the economy, others blamed the rise of alternative games for the gambler’s dollar, such as Lotto (and later Instant Kiwi). Certainly, the expected crowds didn’t come out to Avondale’s racing nights.

By January 1988, the Avondale Jockey Club’s finances were less than completely sound, and the committee were faced with hard decisions. They had enormous debts from the night racing development, and not a lot of income from the venture to show for it. Less than a year after the inauguration of night racing, the secretary/general manager Stephen Penney had a meeting with the Council’s Director of Parks to discuss the possibility of Auckland City Council purchasing 10-14 hectares of the infield areas that they were leasing from the club, at $300,000 per hectare. Discussions also included provision of a $670,000 underpass from Wingate Street to the land should Council purchase it. There had still been no agreement between the Jockey Club and the Council regarding formal renewal of the Council’s lease over the playing fields area.

By June 1988, the Council settled on just having a lease agreement rather than purchasing the land. The Club then offered a lease to last until 2002, with one right of renewal to 2027. Eventually, by March 1989, the Club and the Council came to an agreement, based on the greater of either 5% of agreed value of the land, or the total amount of rates charged to the Club for the racecourse. In 1990, this was around $75,000 per year.

Back in October 1988, the loss made in the Jockey Club’s annual accounts of $1,282,080, plus its interest liability of $998,742 on the $5 million borrowed for the course improvements became public. At their annual general meeting that month, however, none of the 76 members who attended queried the club’s financial performance or situation, the sole question from the floor only being about “the scruffy standard of dress in the members stand,” according to one report. Apart from the attempt to sell a chunk of the infield land to the Council that past year, the club also had plans to develop the corner site at Ash Street and Rosebank Road as a casino, and develop more land along Ash Street for commercial use.

Retiring president Laurie Eccles had just returned before the meeting from giving a paper on night racing at the Asian Racing Conference in Sydney, and told the AJC members they “should not hold any fears over the wisdom of the switch to night racing.” His successor, newly elected president Eddie Doherty is said to have stated, “The financial difficulties were short-term. In a year or two the club would look back and wonder what all the fuss was about.”

By May 1990, when the City Council granted approval to the club to sell off a $600,000 strip of its Wingate Street property for state housing (this though fell through the following month), the club faced a $4 million debt to the Bank of New Zealand who refused to extend the club’s overdraft, and $2.3 million to the Racing Authority. Servicing the loans was costing the club $1 million per year. There was talk of forced amalgamation of the Ellerslie and Avondale clubs to stave off disaster. At the end of that month, Avondale’s race meetings were cancelled until further notice.

The club tried once again to get the council to buy the playing fields, this time for $3 million, but were turned down. In July, discussions began with the bank to try to get them to agree to a rescue package put together by the Racing Authority (where the club’s financial control would be in the hands of an appointed board), but the bank refused. The head of their Credit Recovery Unit was quoted as far afield as Australia: “The Avondale Jockey Club must face the consequences of its own business decisions … It is a business in the same way as a corner dairy, and must accept full responsibility for its financial position.”

A notice of default of payment was issued by the BNZ, set to expire 7 September 1990, at which time the bank would foreclose and sell the racecourse property to the highest bidder. An incredible situation, given that the reported turnover of the club, prior to the racing cancellation, was $50 million per year, the second highest in the country. The club at this point, though, couldn’t even afford to apply for planning permission to have its Ash Street land rezoned for sale, and the BNZ refused to lend them the money to do so.

The Racing Authority and the BNZ eventually came to an agreement which staved off the foreclosure. After the October 1990 annual general meeting for the Avondale club, the bank provided the club with a three year term loan of $2.5 million. The Authority provided the Jockey Club with a further loan of nearly $2 million to pay off creditors and stay within the credit facility offered by the bank, and a three-member Board of Control was put in place to manage the jockey club’s financial affairs. The club resumed racing on 1 November 1990, after shifting a number of their scheduled night fixtures to daytime, with the cooperation of the Greyhound Racing Association and the Racing Conference. The stake for the Avondale Cup was reduced from $250,000 to $100,000, trainers and jockeys agreed to donate their winning percentages to the club, totalisator staff worked for free, and races were sponsored.

The board of control had the power to dispose of portions of the club’s real estate that didn’t interfere with racing operations, in order to reduce the restructured debt. Land at Rosebank Road (Avondale Lifecare) andWingate Street (again, to Housing Corporation), was duly sold. By the time of the October 1992 AGM, the club reported a profit of just over $100,000.

But still more land had to go. The club’s Ash Street property just west of the main entrance was sold in 1995 to Prominent Enterprises Limited, a company which intended to use the land as a golf driving range. This didn’t eventuate, and today the site includes a service station, McDonalds, and Nacton and Sandy Lane residential areas. The 1911 totalisator building finally disappeared.

Most of the area of land that the club decided they didn’t want to gift to the Council back in the late 1940s by the Whau River, was sold in 1995 as well, becoming Corregidor and Michael Foley Place.

From just over 51 hectares or 127 acres at fullest extent in 1944, the racecourse property in 1999 was 36.6 hectares or just over 90 acres.

The racecourse into the 21st century

Then came the message from New Zealand Thoroughbred Racing and the New Zealand Racing Board that they thought that it was better that Auckland have only two racecourses – and Avondale wasn’t one of them. From around 2007, the situation became more fraught, and by 2009 the club had only 13 “industry” meetings, most of them on Wednesdays and featuring moderate horses, and still had $2.5 million in debts.

On 3 July 2010, the club held a final meeting before going into recess yet again. Many Avondale locals popped along, myself included, to say goodbye to what had been, up to that point, such a large part of the local area’s sense of place. We certainly hoped it wouldn’t stay closed.

It didn’t. Racing returned on 25 April 2012, but the debts remained. More land just west of Sandy Lane was proposed for sale in 2014. This took place in 2017, with development yet to begin for 54 terraced homes at Tamora Lane as at the time of writing this article.

Then in July 2018, the Messara Report to the Minister of Racing, Winston Peters, was released. In it, the recommendation was made that Avondale receive no further racing licences from the year 2020/2021. “Venue with 11 meetings in 2017/18. Training. Excellent location. Poor infrastructure. Freehold. Extremely valuable land with an estimated value of more than $200 million with rezoning and which should be sold for the benefit of the entire industry. Avondale JC should race at nearby Ellerslie or possibly Pukekohe.”

After nearly 130 years of racing, surrounded by change both in the industry and in Auckland as a whole, down there on the Avondale Flat it is still a matter of “don’t give up yet.”