Barraud, Charles Decimus 1822-1897 :Maori hack race in full costume. C. D. Barraud del. ; G McCulloch lith. - London ; C F Kell [1877]

Reference Number: B-080-031-2-2

Two young Maori men racing horses, one clad only in a shirt, the other in cap, open-fronted shirt shirt and jodhpurs. Alexander Turnbull Library.

From c.1894 to c.1908, there was once organised horse racing meetings at Orakei, behind the settlement at Okahu Bay. For Aucklanders in the 1890s to early years of last century, these country meetings would have provided both a destination for excursions out over the Waitemata Harbour to the wharf at Takaparawha Point -- and a source of entertainment, beyond just the thrill of the bet.

The settlement at Okahu Bay, 1920s. Ref. 4-4439, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries

Auckland Star 22 December 1894

Auckland Star 5 March 1898

What drew my attention to the story of the Orakei races was the following long descriptive and lively piece from the NZ Herald.

This is a true story of a day at the Orakei race meeting.

A hot sun beamed down upon the little breeze-cooled valley, at the seaward end of which the Maori settlement lay lazily fronting the still waters of the bay. At the rear of the village an open space surrounded on three sides by rising ground, which formed a natural coliseum, wore an animated appearance on Saturday last as a guileless representative of the Herald jumped a muddy creek and joined the crowd of people there assembled. The usual fraternity to be seen “on the outside” at other race meetings had foregathered – two or three hundred of them – ranging from the city man to shabby tout. In and out amongst the throng passed Maori officials, phlegmatic, gravely, and with infinite circumlocution going about their various businesses, as though serious matters were afoot, but there was no hurry. The uninitiated pressman commenced to take his bearings.

Nothing visible was there to indicate where the races were to be run from or to, where the numbers were to go up, or from whence the flag signals were to be flown. In the middle of the ground a large Maori, in a wideawake straw hat and his shirt-sleeves, was helping two wahines to supply thirsty visitors with “soft tack” and watermelon. To him the scribe appealed. The large Maori turned out to be the secretary – a most obliging person – but preoccupied. He pointed out a shed at a little distance where, between two roughly nailed-up bits of kauri, three mystic numbers had been hung. “That the first race,” he said; “three starters.”

Oh,” said his questioner, “and where do they stick up the results?”

Same place,” was the laconic reply.

THE “BOOKIES” SCORE

At that stage one of a group of men carrying large bags, which jingled when they moved, accosted the secretary. “You’d better take it while you can get it,” he said. “None of them will bet if you insist on the ‘two ten’ racket.”

Then the pressman remembered having seen an advertisement, which set forth that bookmakers desiring to bet at this meeting must pay £2 10s for a license, or “stay at home”. They had refused to be domestic, but were in no mood to let their outing cost them more than was necessary. At their spokesman’s blunt statement of the case the preoccupied one fought a silent battle with himself. Good-nature – or was it business instinct? – won the day. “All right,” he ejaculated with startling suddenness, “announce it.”

“Boys,” said the bookies’ representative, in a loud, triumphant voice, “you can bet for a pound.”

“An one shillin’,” chipped in the astute secretary.

“A guinea, boys,” corrected the bettors’ mouthpiece; “come on, pay up, and get a start.”

And they did. Within a few minutes the familiar cry of “Even money on the field” resounded in the air.

Over towards the little shed a native official walked serenely around, looking for the starters for the first race. An old fellow in a white suit acted as his “go between,” and helped to saddle the three horses when they had been found. In the shed upon which appeared the numbers the three riders donned their colours. This was a very useful shed – everybody used it – jockeys, stewards, and public. It was weighing-in room, dressing-room, and stewards’ stand in one. Out of it popped a Maori horseman. He wore a scarlet jacket, with a white stripe, and a pair of long pants. “Lend me a coat,” he cried; “I got to make up 3lb.” Someone filled the order, and he put it on, the tails of the red jacket jauntily flying in the wind from beneath it as he rode away.

Then came the preliminary canter. A comfortable-looking Maori on a sturdy pony cleared the course, which was merely an unevenly trodden track around the pa. The three candidates for a stake of four sovereigns rattled down the straight amidst the cheers of the crowd. Dogs of all sizes and descriptions, awakened from drowsy slumbers by the noise of the clattering hoofs, scuttled down the hill-sides, rushed blindly from diverse bushes, and dived madly yapping, into the clouds of dust raised by the disappearing steeds. Away on the other side of the valley the three riders pulled up. The starter on a Maori “scrubber” got them into line, and hit his hip.

“They’re off,” yelled the people on the rise, from sheltering tea-tree, and the like. The crowd on the green made a rush for the track, and several crossed and ascended to points of vantage. This, of course, gave the clerk of the course some work to do. He did it with as little exercise of muscle and tissue as possible, merely sitting statuesquely on his pony and issuing commands to “keep back there,” like a captain on the bridge. The first time past the winning post, and it was clear to most of the spectators that the chestnut mare must win. She had a lead of many yards, and the other two were, as the racing writer puts it, “under punishment”. Roars of delighted laughter rent the air as the pakehas saw the gallant mare run along the back like the wind, her opponents furlongs to the rear. At the bend her rider pulled her up to an easy amble, and at that pace passed the post, the others nowhere.

“Another round,” shouted some wit in the crowd.

“Yes, another round” – a hundred voices joined in the cry.

The jockeys on the last two horses, who had made a merry “go” of it for second place, were quite willing but as they were about to whip their mounts into renewed efforts, the judge climbed down off his hencoop, and remarked finally, “All over.”

So the crowd was baulked.

Maori group (at a country horse racing meeting?), [ca 1901]

Reference Number: 1/1-001882-G

Maori group (at a country horse racing meeting?), circa 1901. Photograph taken by the Auckland studio of Hemus and Hanna, probably in the Auckland region.Alexander Turnbull Library.

HORSE OR PONY?

The horse is a sagacious animal. Someone has uttered the same remark before, but that does not make it any the less true. An instance of the sagacity of a horse who was entered for a pony race will now be given. The story of this pony race deserves to go down in posterity in the form of profuse illustrations and accompanying text, a la “Darktown Races” series. It was the third race of the day. The pressman had received priceless information as to the two former events from a small boy with a black body, a red tie, and a white nature. He learnt from him in consultation prior to the pony race that the best “horse” in it was a certain bay mare. “But,” said the knowing youth, “if she wins she’ll be measured after the race.”

Now, the unsophisticated scribe hadn’t the remotest idea why it would not be good for the bay mare to be measured, but he winked slyly at his young friend to cover up any sign of ignorance he may have displayed. The mystery was explained afterwards. To commence with, there was what the pressman would have described as a bad start. The starter had scarcely smacked his hip before the bay mare rose up on her hind legs, with her mouth open. When she did get away she was well in the rear. Curiously enough she forgot to shut her mouth again during the race, and this induced some unkind people to say nasty things about the jockey. That measuring business was blamed for it too. Anyway, the brown gelding won. He was having his photograph taken, with the proud owner “up” when there came a swirl of the crowd towards the stewards’ dressing-weighing shed, and a heated Maori on the grey gelding, which had run second, urged his nag towards the shed door with a cry of “protest” on his lips.

Someone stuck a tattered and faded flag up over the lintel of the door. “What’s the blue flag for?” asked a spectator on the outskirts of the now jocularly excited crowd.

“Blue,” scoffed the man nearest to him. “It’s green. There’s a protest.”

A Maori of proportions which a Frenchman would describe as “embonpoint”, leisurely thrust his huge bulk through the mass of pakeha spectators who were storming the shed in their desire to hear the fun. “where are the stewards?” he said. From several points of the compass coatless Maoris, figuring in the required capacity on the programme, edged their way into the shed of many uses.

“Run it again, no race,” yelled the mob deliriously.

Out on the green, stamping a profusion of penny-royal beneath his feet, and thereby filling the adjacent air with the pungent smell of peppermint, a Maori backer of the bay mare waxed wrath. “Wha’ for?” he gesticulated.

“No race, I tell you. I go for the police. The mouth came like that – wide open.” And he proceeded to give an imitation with his hands of the open mouth of a horse.

Whilst the stewards were in the shed deliberating over the protest, a pakeha official (self-constituted, unless the race-card lied) was measuring the grey that had come in second. A length of timber, with a rough cross piece nailed on at a pony’s lawful height, was requisitioned. The grey passed comfortably beneath it, amidst cheers from the onlookers.

Then the winner was wanted. He had disappeared. Not a whinny betrayed his hiding place. Fast sped the moments, but he could not be found. The scribe was beginning to wonder if it could be possible, as was hinted in some quarters, that the owner did not want the brown measured. Of a sudden an exultant yell arose. “Here he is!” and someone dived into a clump of willows, and dragged forth the missing quadruped. Was it a horse or a pony? The all-important question took a lot of settling. Eventually the man with the stick declared that it failed by three or four inches to pass under the crossbar. The news was broken to the stewards, who were about to decide that the protest must be upheld, when the owner of the horse that had been declared not to be a pony appealed to the secretary, nearly coming to blows with an angry member of the crowd whose money was on the grey. The secretary, assuming supreme powers, and over-riding those of the stewards, seized the measuring stick. The people surged round him, and the brown gelding sent them scattering with uplifted hoofs. He seemed to dread that measuring-stick. He would not stand still. Ultimately the sagacious animal espied a ditch. He promptly stood in the bottom of it – stood there like a lamb. The timber measure was placed on the ground. It rested on the bank of the ditch, as the gelding has designed that it should. The crossbar showed inches above his back. “He’s pony all right,” decided the secretary, flinging the stick down, and the gelding was seen to furtively wink at his owner as the latter led him away. In the shout that went up were mingled execrations. One man said something reflecting on the secretary. But the secretary – he who had so firmly carried out his work, and with such supreme contempt for all other authority – said nothing. It was not his fault if the brown gelding did stand in a ditch. It merely proved that a horse’s sagacity is equal even to making out that he is a pony.

THE DISAPPEARING JOCKEY

The running of the Orakei Cup of 9 sovs was another feature of the meeting that was not without interest. Hard-hearted people declared that it was a “schlenter”, whatever that may mean. They said that the horse that was leading most of the way was not meant to win, and that the horse in second position for the greater part of the distance was. As it turned out, a Maori horse, which, cruel report had it, was blocked all the way, got home first, and there was great glee amongst the natives in consequence.

Just before the three horses entered the straight the jockey of the leader, who was running strongly, disappeared. When he limped painfully into the open space where the crowd was, a little later, with sand in his hair and a woebegone expression, he was heartily jeered.

“Booh,” remarked a Maori in his ear, with infinite scorn, “you jump off the horse. Wha’ for?”

The poor jockey, with a “not understood” expression, wildly resented the aspersion, but the spectators showed a similar spirit to that of the Maori accuser, though they were good-natured enough about it. The fact that the rider “left” his saddle in a nice, soft, sandy place was beyond doubt true, but how the poor young man must have suffered to hear someone say that he had rubbed the sand into his head and gone voluntarily lame!

The element of happy-go-lucky haphazard ruled everything. Maori riders cheerfully went “another round” when the spectators urged them to do so. The clerk of the course most agreeably furnished reliable tips to all inquiring investors, and so did all the other inhabitants of the village. Wahines strolled around in gaudy greens and resplendent yellows; mongrels chased the racers round the course; children romped, and everybody was in a laughing mood.

The difference between the Orakei races and musical farce-comedy is that in one case there is no music.

NZ Herald, 20.1.1908

Programme advertising a Maori horse racing meeting in Karioi, Waikato, 1 January 1870

Reference Number: 1/1-000855-F

Programme advertising a Maori horse racing in Karioi (Whaingaroa/Raglan region) January 1, 1870.Alexander Turnbull Library.

The end of 1908. though, seems to have been the end of this part of Auckland's horse racing history.

A MAORI RACE MEETINGLUDICROUS INCIDENTS AT ORAKEI.[From Our Correspondent.]AUCKLAND, December 26.For some time past there had been portentous signs of trouble for the Maori Christmas Day races at Orakei. Mysterious and contrary advertisements had assured bewildered race goers that the race meeting would and would not take place. Intending patrons were definitely told that an eighteen-penny fare would admit them to the course and in the next advertisement they were informed that if they set foot on the course on Christmas Day they would be prosecuted as trespassers. An interesting account of the sequel is given in the Herald report of the races.When the racegoers went to catch the ferry steamer to Orakei they were confronted by a remarkable notice, which conveyed the information that the course had been ploughed up, by whom it was not stated. Notwithstanding this depressing manifesto large numbers went out anticipating some fun. They were not altogether disappointed. The course had been ploughed up right enough. The situation was earnestly discussed by many Maori but nobody seemed to be able to indicate the perpetrator of the fell deed but the Maoris who had gathered together for horse racing were not going to be stopped by a trifle like the want of a course. Some ingenious brown individual pointed out that the stretch of beach would do as a makeshift, and the joyful news that races were to be held was spread abroad and the first race was started.There were horses of sorts from the twelve hand pony to the seventeen hand horse that would have looked more at home in a spring cart. There were also a few good ones in the motley lot. They went up under the cliff to start, about twenty-five of them, but they were thinned out. Three bolted off and had a race of their own. Several dashed into the sea, two darted across a field and were seen no more. Then a vicious little pony scratched at least three for all engagements with hind hoofs, in making room for himself. One horse started to browse so greedily that his rider could not get his head up and was left at the post. They started, or some of them did. The field swept along in gallant style, some in the water and some out of it. A desperate finish ensued. As the ti-tree winning-post was neared, the tumultuous mob cheered madly, the struggle was terrific, but blood told. A dashing little animal, pakeha rider up, finishing gamely under punishment, just got his nose in front of the hope of the Maoris, a long raking bay beast ridden by a barefooted Maori boy."No race"' It was the voice of a Maori judge who sat still and impassive in all the excitement, sheltered from the rain by a huge umbrella. There was a furious outburst of wrath from the pakeha rider.“No race be damned! This is a bit tough. Why, I won the race fair enough."“They didn't all start," said the judge.“Well, the starter gave to the word to go and we came away. Why, some of them are messing about there, I ain’t to blame for that, am I?” The judge declined to argue the question further. He called up the starter, who had paced along with the field, probably to see that they raced fair, and in a dignified tone demanded an explanation. The starter gave a loquacious account of affairs that apparently satisfied the judge, and he ordered the race to be run again. He also showed his supreme authority by limiting the number of the field.“Six of them no more," was his brief mandate to the starter.There were more races, including an event which was dignified with the title of the Orakei Cup, but one Maori horse race is very like another, and the pakeha spectators who had gone out from curiosity began to drift back to the wharf for the ferry boat.

Christchurch Star 28.12.1908

Around 1914, the sewer line was installed along the shore of Okahu Bay. Native Land Court judgements and government legislation began the breakup of the Maori-owned lands at Orakei, and the days of the "anything goes" races were gone forever.

If the one-time Maori race meetings were still being held at Orakei it might be worth while keeping some of the horses who raced at Ellerslie in training.

NZ Truth 15.6.1918

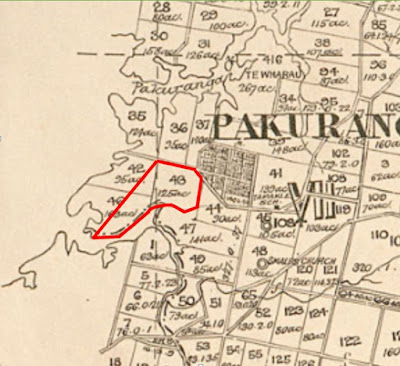

Detail from NZ Map 7013, 1920s, from Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries