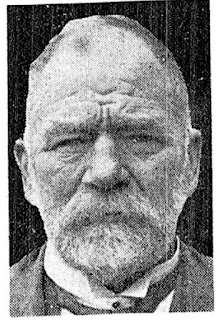

Image: NZ Herald 3 August 1927Here is a man for whom the legacy, 160 years after his birth, of the enduring fame he had intended for himself has become muddled with that of a possibly namesake nephew. A man he pointedly declined to recognise as an heir to his will. Said legacy has distinctly faded over time.

The fame is slowly drifting away into the mists of lost memory; the arch bearing his name across a gateway to the tennis grounds at 335 Point Chevalier Road, that was removed between 2013 and 2015, had not been restored and put back as at April 2021. While there still is an incorporated society bearing his name that administers the main building on the sports ground there (and the name remains as a condition of his “gift”), the tennis, bowling and croquet clubs have not carried his name for decades (although the croquet club still retains “HJ” at the top of their logo.)

The sports grounds at Point Chevalier were not even truly “gifted” to the community or to the three sporting codes that occupy the space. While he was alive, Johnstone retained his title over the property, and received a £200 annuity payment (reduced to £104 per annum if paid punctually). Johnstone’s interest in the property, in the 1930s, was listed in the society accounts as a £1000 liability. He was a life member of the trusts executive committee, and personally chose three of the trust members out of the six places. When he died the title for the grounds was passed on to his executors, then to his solicitor Frederick Coles Jordan (one of the trustees Johnstone had appointed) and was then placed with the Public Trust Office. The annual rates bill charged for the now $4.2million property (just over $10,000) is shared in proportions by the three sports clubs. Should the clubs fold, in accordance with the deed from 1927, then the land will go to Auckland Council.

Arch that was above the Pt Chevalier Road entrance to the sports ground. Note incorrect space in Johnstone's first name on the sign. Image 2011 by Phil Braithwaite.

There were four major trophy shields bearing Johnstone’s name: one for the Auckland Rifle Shooting Championship, one for the Waitemata Swimming Club Harbour Swim Competition, one for the Auckland Soccer Minor Associations tournament, and one for one-day Domestic Women’s Cricket. Only the last remains in use and awarded annually – although from 1982 until 2017, it had been replaced by the Hansell’s Cup, before being reinstated.

NZ Rowing still do have a cup competition in his name, known these days as the Hallyburton Johnstone Rose Bowl. This was described in November 1927 as “a massive bowl of silver … originally the property of the Duke of Buccleuch,” acquired by Johnstone on a visit to England. Even this year, one major South Island newspaper’s journalist mistakenly thought that the nephew’s generosity should be praised for its existence, not that of the uncle.

Johnstone was born on 15 January 1862 in Raglan, on the west coast of the Waikato region. His first name came from his paternal great-grandmother, Magdalene Hallyburton, back in the county of Fife, Scotland, in the 18th century. His father John Campbell Johnstone joined the military life, employed by the East India Company in 1834; by the time he resigned in 1853 he had held the rank of Captain for three years. According to a family history, land was what drew Captain Johnstone to New Zealand. There is speculation that he may have had contact with up-and-coming land barons here, namely William Brown and Dr John Logan Campbell, as to what was available from out of the dealings taking place at the time between the government and Maori. At that point, there were land deals being made near Raglan, and these drew Captain Johnstone to that part of the island. Unfortunately, there were misunderstandings between the Crown and the Maori land owners, with Captain Johnstone in the middle of that fraught sandwich.

He did manage to set up his Te Haroto sheep run to the east of the Raglan township, but there were years of compensation applications, not to mention the Waikato War of the early 1860s. The Johnstone family left Raglan in June 1863 and took up temporary residence at Waiuku, returning in September 1864. Hallyburton (born 1862) was the eldest son. His brother Campbell was born in December 1863, and brother Lindsay in May 1866. There were other siblings, but these three brothers and their relationship were later to become national news.

Captain Johnstone died by his own hand in 1882, in the midst of a bitter dispute with a committee over a local school site of all things. His farm remained in family ownership until around 1914, but his homestead burned down in the early 1890s. In his will dated 1874, he railed against the Government policy of borrowing money from England and adding to the colony’s debt. His son Hallyburton would come to follow in his father’s footsteps in terms of using a last will and testament for personal commentary and criticism.

Hallyburton, Campbell and Lindsay were close. All three of the brothers took part together as members of the Te Awamutu Volunteer Cavalry before Hallyburton left to spend a few years in Canada in 1888. On his return in 1894, that close relationship was taken up again. Campbell’s son Hallyburton was born in 1897, named after his uncle.

The brothers took up leasehold land at Whatawhata, and near Ngatea on the Hauraki Plains. Lindsay acquired over 900 acres there in 1909. Hallyburton financed the development of the farms, and his interest was registered by the lease being placed in his name. Campbell and Lindsay then acquired adjoining properties; Hallyburton advanced his brothers more funds, and thus those properties were put into his name as well.

By that stage, Hallyburton had made his fortune through the sharemarket, then extended his financial portfolio to land dealings. His first wife Sophie (15 years his senior) drowned in 1896, the same year he’d started his interest in gold, coal and dredging company shares. There has been speculation that her own fortune greatly assisted him. After Sophie’s death, Hallyburton senior lived at his late wife’s Port Waikato home for a time, then acquired 55 acres near Waiuku by 1904. In 1907 he was farming at Aka Aka, and in 1909 was taking part in the Waiuku Tennis Club on the combined tennis, bowls and croquet ground.

In 1911, the mother of the Johnstone brothers passed away. Then, in July 1915, Lindsay drowned in a flood of the Waipa River. Suddenly, the dynamic of the brothers’ partnership regarding their 1909 land dealings changed.

Earlier in 1915, Hallyburton sold part of the land on the Hauraki Plains he’d held in trust for himself and his two brothers for £10,023, and received a deposit of £500. Ultimately, the buyer defaulted, paid nothing further, and Hallyburton retained the £500 for himself. He did successfully sell the property eventually, for £10,000, but kept that money as well. Later, Campbell and Hallyburton came to a series of verbal agreements over this and other lands held by the brothers, where it was agreed that interest in the properties would pass from Hallyburton to his siblings in return for the money he had held onto. Hallyburton later denied this in court in 1917; eventually he, Campbell and Lindsay’s widow came an out-of-court settlement.

This did not stop the legal actions, though, merely postponed them. In 1924, the partnership’s accounts came before the Supreme Court in Auckland, and an agreement was signed. Then, in 1928, Hallyburton announced that the agreement document he’d signed four years earlier was not what he had agreed to at all, that he had been defrauded just over £14,000 over the amount he’d said he would pay to settle Campbell and Lindsay’s widow’s claim. He tried petitioning Parliament to overturn this, to no avail.

A year later, in 1929, there was another court case (this time against his brother Campbell), where he claimed that he was owed £33, his share of the sale of their father’s Raglan farm, plus interest on his 1/6th share of the estate. “I had carried [Campbell] on my back for years, but he would not give me a penny,” Hallyburton declared. “I have never received a cheque from my brother in his life, and I have given him dozens.” He denied the 1909 land partnership ever existed, describing the agreements with his brothers purely as a business situation. Still, he lost the case, and had to pay costs. After hearing the judgment, he then angrily made another accusation against Campbell; the judge warned that if he didn’t keep quiet, he’d be removed from the court.

Hallyburton wasn’t about to leave things there, however. Straight after the court hearing, he proceeded to harass his brother Campbell, sending envelopes address to him care of the bodies upon which Campbell sat as a representative: the Auckland Harbour Board, the Raglan County Council and the Waikato Hospital Board. On each envelope was written, “Campbell Johnstone, the man who pleads the statute of limitations.” These sparked another court hearing, and Hallyburton was bound over by the judge to the sum of £10 that he would cease sending such wording on envelopes to Campbell ever again.

Campbell died in 1930. Hallyburton was thus afforded the final say on things, via one of the paragraphs in his long will, complete with two codicils, probated in 1949-1950. A dead man defaming other dead men:

“I further desire it to be known that the reason why I have omitted to name the children of my late brothers Campbell Johnstone and Lindsay Johnstone as beneficiaries under this my will is that in my opinion such brothers unjustifiably instituted legal proceedings against me for the recovery of moneys from me and defrauded me of over £14,000.”

At the time the sports ground in Pt Chevalier was inaugurated, it is said that a set of minutes noted an explanation for Hallyburton’s lack of outright gifting of the site to the community. This explanation brought up some circumstance where it was claimed a similar piece of land he’d gifted in Waiuku had instead become lost through mortgages in 1920. Actually, I’ve yet to find anything like that happening in Waiuku – but there would have been a lot of precedent otherwise for Hallyburton’s determination not to let go of the Pt Chevalier site until his own death, from his own background in dealings with his brothers and their heirs, and his opinion that he had been “swindled”.

Unfortunately for the clarity of Hallyburton Johnstone senior’s legacy, his nephew by the same name had a more notable career, which is why the two are often today mixed up. Campbell’s son Hallyburton junior, born 1897, served in the NZEF during the First World War, and went on to farm sheep and cattle in the Raglan area. He won the Raglan electorate seat in a 1946 by-election for the National Party, lost it in the general election, then won it back in 1949. He then contested the Waipa seat in 1957, won, and only retired in 1963. He was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1966 for farming and his political career, and died in 1970.

Some other parts to Hallyburton Johnstone senior’s life:

After his first wife, he married twice more, both marriages ending in divorce, dissolution, and more court cases. In 1909, he married Margaret Isabel Jollie; this time Margaret was five years younger than he was. That year, Johnstone purchased a house at Howick called “Ingledell”, and renamed it “Elkholm” (probably after his passion for deer shooting.) This became Margaret’s home from 1911 while he spent most of his time in Ngatea, Margaret refusing to consummate the marriage due to a “physical defect” of some sort (according to the 1918 divorce application from Hallyburton Johnstone, said defect probably a heart condition). In 1915, Margaret offered up “Elkholm” as a possible site for invalid soldier accommodation. The 1918 application for a divorce didn’t succeed, but Margaret’s own 1924 application on the grounds of desertion did. The house and grounds were sold in 1924 to the Catholic Church; as one of the “Star of the Sea” convent buildings there, it burned to the ground in 1929.

“Ingledell” on Granger Road at Howick, renamed “Elkholm” by Johnstone, which became his second wife Margaret’s residence. First built in the late 1880s, the house is seen here just after purchase by the Catholic Diocese.

Footprints 02004, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.

In 1935, Johnstone married for the third and last time, to Mary Mitchell Cooper, 22 years his junior. Two years later, in 1937, Mary refused him any conjugal rights. He took the matter to court, where Mary was ordered to resume said rights, but she still refused, and also refused to return to live with him at his Alford Street home in Waterview. The marriage was dissolved in 1938.

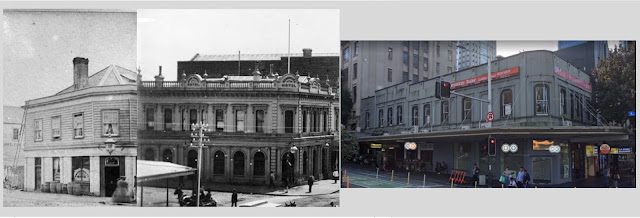

Johnstone first became involved with Pt Chevalier land dealings in 1911, when he bought nearly 18 acres from James Dignan, and had his “Town of Meola Extension No. 3” surveyed, forming Johnstone Road (named after himself), Bollard Road (after John Bollard the local MP – now Boscawen Road), Bungalow Avenue, and Bella Vista Terrace (now Bangor Street). It took from 1911 to 1938 to sell all the sections, but many he may have been renting out for income during the period.

In 1920, Johnstone picked up two 1/10th shares of the remainder of the Liverpool Estate Syndicate from the bankrupted Thomas Dignan, and from land agent Sydney Valentine Mack. The sections (including the “bird” streets) were finally completely sold or otherwise disposed of in 1927. Johnstone transferred his interest to Francis John Dignan just before the last section was sold.

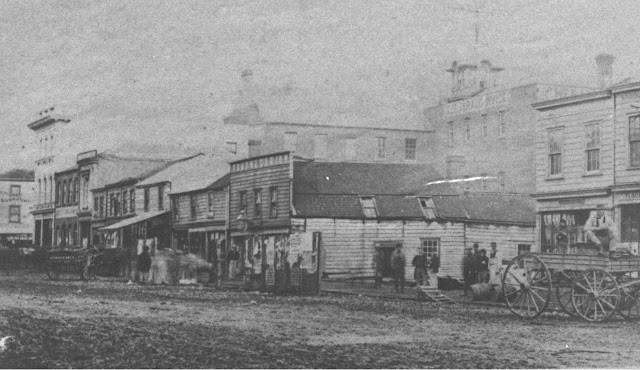

Hallyburton Johnstone (inset) and the property formerly owned by Thomas Dignan in Pt Chevalier over which he formed the sports trust. Auckland Sun, 3 August 1927.

It was also in 1920 that Johnstone bought six and a quarter acres of Thomas Dignan’s “The Pines” farm between Pt Chevalier, Dignan and (the future part of) Walmer Road, also due to Dignan’s bankruptcy. Johnstone arranged for a survey in 1922 – interestingly at that point setting aside the same three main portions of the property (just over four acres) which form the property now used by the sports clubs. Johnstone moved from Ngatea to Dignan Street in 1924, around the time of his first divorce. The two mortgages on the property from Thomas Dignan’s ownership weren’t discharged by Johnstone until May 1927. Three months later, Johnstone’s “gift” of the site was announced.

Johnstone had held political offices before his shift to Auckland from Ngatea in 1924. He’d been on the Raglan Road Board, the Waiuku Drainage Board, Thames Hospital Board, and served as chairman of the Hauraki Plains War Memorial Committee. In April 1927, as an independent, he made an unsuccessful run for a seat on the Auckland City Council.

Then after his move to Alford Street in Waterview he ran again, as one of the “Independent Eleven” in April 1929. It may not have helped that he switched horses midstream, as it were, just a week later to join Allum’s “People’s Welfare” ticket. Yes, he lost the election that year.

The following year was brighter for him, though, as he was chosen to accompany the NZ bowls team to the Empire Games in Canada. This must have been a real highlight for him, travelling back to the country where he’d earlier stayed in the late 19th century and worked on a cousin’s farm near Vancouver. He returned by early November 1930, and was interviewed by the press as to his impressions of Canada, California and other parts of the US, which must have delighted him. He even offered to be an intermediary for a trade in zoo animals between Auckland and zoos in North America.

The 1930s and 1940s, also, was a time when, with the Pt Chevalier Bowling Club calling itself “Hallyburton Johnstone,” Johnstone’s name was spread throughout the pages of newspapers covering tournaments, with commonplace headlines like “Hallyburton Johnstone v. Henderson” for reports on district games.

At the end of it all though, after the failure of his third marriage and with increasing ill-health as he entered his eighties, Johnstone began to make mistakes which cut deeply into his accrued fortune. His astuteness in terms of property details began to leave him. Family recollections indicate he lost considerably on a number of later Auckland commercial deals. Certainly, he became involved in court actions over rent arrears owed to him. His main will was made out in 1941, but was followed by two codicils in 1948 drastically reducing promised bequest amounts. When he died, though, his final net worth was still recorded for probate purposes in 1952 as £33,370 5s 9d, roughly $2 million today.

What to say about Hallyburton Johnstone (1862-1949)? He certainly enriched local sport in Pt Chevalier, whether one thinks the land there on Dignan Street was a gift or not; thanks to the availability of somewhere to play, the clubs were able to form, and have had a home ever since. His general love of sport extended to cricket and rowing, via the silverware he donated. More of his silverware collection apparently was displayed in Centennial Street at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, although whether the museum still retains it is not now known.

It is a pity the named archway hasn’t been replaced at the Point Chevalier Road frontage, but at least he hasn’t quite been forgotten. With a name like Hallyburton Johnstone (now and then seen with a hyphen, as if that was all his surname, or he was actually two people!) – how could he be?