Avondale market gardens

From 1905, Avondale market gardener William Knight appears to have had issues with regard to Ah Chee’s Avondale business. On Sunday 12 February, he watched workers at Ah Chee’s gardens tending the crops and harvesting. Obviously incensed, he wrote the following letter to the Auckland Star, published 14 February.

“Sir,—Will you kindly allow me to refer to the closing sentence of your sub-leader on "Alien Immigration" 'in Thursday's "Star," which says: "But the tendency of such movements of population is always the same, and if we wish to escape the attendant evils we must look to it that our workers shall not be subjected to unfair competition at the hands of aliens content with a lower wage or a lower standard of comfort., be they Oriental or European." Now, sir, this is the very state of things that exists at the present time in the market gardening in and around Auckland. On what is commonly known as the Avondale Flat, or North Avondale, there are now a large number of Chinese working. The long hours which they work, the low wages they get, the insanitary conditions under which they live, and their being allowed to work on Sunday as on any other day places them in a position that it is almost impossible tor the European to successfully compete with. Quite a number of white people have been replaced by Chinese. In one instance recently a Chinese gardener was advertised for, a white man being discharged, and a Chinese taken on in his place, and some others are thinking of doing likewise. Now, sir, these long hours, low wages, insanitary conditions, and Sunday labour enable growers who have the advantage of them to secure the contracts for the supply of vegetables to the many steamboats that are constantly leaving Auckland and Onehunga and in other ways undersell us. Our sons, as they grow up, are compelled to leave the home and district and seek work elsewhere, while Chinese come and take their places: and they are bold enough to say that we cannot stop them from working on Sundays because they have to supply the boats. —I am, etc, W. KNIGHT, Avondale.”

In March that year, he appeared as a witness for the prosecution at a police court hearing where ten Chinese gardeners at Ah Chee’s property were charged with “following their calling within the public view” on Sunday, 12 February. Their names, as reported at the first hearing on 22 February, were given as Ah Lee, George Duck, Ah Sun, Hing Yong, Kam Wah, Ah Ping, Ling, George Ling, William J Linton, and Alfred W Linton, Knight testified that he’d seen them “pulling and hoeing vegetables on Sundays” many times. W J Napier, defending the gardeners, raised an interesting point.

“Mr. Napier submitted that the defendants, who were employed by a contractor named Ah Chee, only pulled and bagged vegetables on Sundays which were required early on Monday mornings. It was impossible to deliver them in time on Mondays unless this was done, as Ah Chee undertook to supply a large number of steamers leaving at that time. He contended that merely pulling and bagging vegetables was not following their ordinary calling, which was that of hoeing and manuring the vegetables, and that it could be regarded as a work of necessity. He called Ah Chee to produce vouchers, showing that on the morning following the particular Sunday he had to supply fresh vegetables to seven of the Northern Steamship Company's steamers. The practice now complained of had gone on without question for twenty years.

“Mr. McCarthy, S.M., who heard the case, decided that Mr. Napier's contention was correct. He remarked that on the score of health vegetables must generally be freshly pulled, and it was a necessity that people in hotels and on steamers should be fed. Taking all the facts into consideration he found that the Chinese came within the exception allowed by the Act, and he dismissed the information.”

(Star, 2 March 1905)

But, the campaign against the Chinese working on Sundays at Avondale campaign didn’t stop there. Eight of Ah Chee’s workers appeared at the Police Court in November 1907 to answer charges. Mr Napier, once again defending, told the court that Ah Chee “had something like 50 contracts to fill every Monday morning to various steamers and clubs”, so the men had to work on Sunday to pull the vegetables fresh from the ground. The men were also charged for tending and weeding the potato crop, in clear view of a country road on a Sunday – in this case, Rosebank Road. The second charge was dismissed by the magistrate at the end of November, who viewed that the law allowed for the work of tending the potatoes seeing as the weather had been extremely wet, and that weekend was the first fine break in quite some days. But, the magistrate disagreed with his colleague’s 1905 decision, and ruled that the vegetables for the steamers and hotels should have been pulled up out of the ground on Monday, instead of Sunday, so declaring that the workers had broken the law, the Police Offenses Act 1884. They were fined 5/- with costs, each. (Star, 4 and 30 November, 1907)

The newspapers periodically reported more cases of Chinese working down Rosebank Road on Sundays – and being fined – who may or may not have been connected with Ah Chee’s Avondale gardens.

In 1920, however, it appears the workers went on strike for better pay – and took the train to most likely Ah Chee’s store in the city to express their views.

"Hoolahi whampoa mukka hilo, mo tenksch!" At least it sounded like that, and there was a good deal more of the same sort of thing from the band of Chinamen (all in their best bib and tucker, clean boots, and collars, with no sign of the market garden about them), that invaded Auckland yesterday by train from Avondale, the home of the early cabbage and giant turnip. Various surmises were for this Celestial irruption, from the finale to a social "dust-up" in suburban tiding circles to a fete day in connection with one of other of the two bodies politic into which the Flowery Land is at present divided.

“When the voluble party reached the Auckland railway station it made for the premises of a well-known Chinese firm, and later the deputation emerged with the ghost of a smile flickering round its various features. It turns out that there was nothing political or of a festive nature connected with the visit. The Celestials were merely in the fashion. They were on strike. Hanging up the hoe, and placing the long-handled shovel in the corner they bought second-class return tickets, and seeking out the "boss" explained that they wanted more pay, and until the matter was settled the lettuces and cauliflowers had to look after themselves. There was no question of hours, so fortunately the dispute was not double-barrelled —that bug-bear of the Court and Council. After a full explanation of the position the terms of the agriculturists were granted, and it is stated they now draw from £2 to £2 5/ a week, have quarters free, and food thrown in.

“This makes the third time the gardeners have been out, and about the only thing left that will not strike must be the Japanese wooden matches now on the market. The Chinamen don't bother about registering under the Arbitration Act, but have their unions nevertheless; probably all the stronger because they are more or less secret. The Chinaman has always had a predilection for the secret society, and adopts the same procedure in his labour agitations. He doesn't worry the Press with reports of his meetings or pass resolutions demanding the intervention of the Minister of Labour, but achieves his object all the same. Anyhow for the present peace once more reigns in the potato rows at Avondale, and John is this morning once more hoeing into it again with very nearly a grin on his inscrutable "dial."

(Star 16 March 1920)

Mechanic’s Bay market garden

In January 1916, the Hospital and Charitable Aid Board were approached by a deputation from the Northern Union Football League regarding the hospital land at Mechanic’s bay, at that time leased by Ah Chee for his market gardens.

“The chairman of the Board (Mr Coyle) said the land in question was at present leased to Mr Ah Chee. The lease would expire next June, but Mr Ah Chee had an option of renewal for another fourteen years by paying 5 per cent upon the capital value of the property. Some two or three years ago the value was fixed at £5,000, but now it would be more than that amount.

“Mr E H Potter said he was glad the club wished to get this site for a sports ground. It was an ideal property for such a purpose.

“Mr Wallace said the club was out to encourage clean sport. It was the Board's duty to do all it could to help the club. Mr G. Knight said all of them were in sympathy with the deputation in the request made, but the ground was leased at the present time, and that might be renewed. At this stage the Board went into committee, and upon resuming, it was announced that the question had been referred to the Finance Committee to report.” (Star, 26 January)

The Board decided to offer a 15 year lease to the Club for the ground in May 1916 (Star, 5 May), and Ah Chee called for a conference on site that August “to deal with several matters in connection with the taking over of the property.” (Star 31 August) In July 1917, Ah Chee applied to the Board for an extension of his lease, clearly not about to part with his first gardens just yet. The Board referred the application to the League Club. (Star, 26 July)

The end of Ah Chee's first Auckland market garden, and the foundation of much of his business portfolio, came in 1920.

Auckland Rugby League hae now acquired the playing ground for which it has been negotiating for some considerable time. Last evening the Auckland Hospital Board granted the League the lease of the land now occupied by a Chinese gardener. The property, six acres in area, is situated in Stanley Street, immediately adjoining the Domain, and the rental, on renewable Glasgow lease, has been fixed at £140 a year for the first four years, and £320 a year for the balance of the first twenty-one years.

(Star 22 September 1920)

The end of Ah Chee's garden, the beginnings of Carlaw Park. Images 7-A13262 and 7-A13263 joined together, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Library

Poll Tax evaders

Ah Chee’s tobacco farm at Mangere belonged in the 19th century. In the 20th century, the firm was back at Mangere, this time with a more conventional market garden. Two Chinese labourers were arrested there, apparently after having been smuggled into the country in April 1919. Ah Chee Bros. denied knowledge of them. (Star, 26 April) By May, the case had expanded, after the two labourers were fined £10 “for landing in New Zealand, for evading the poll tax.” Now, the defendant before the Police Court was Ah Chee’s nephew Sai Louie.

“The offence went back to the night of March 15 last, when two young Chinese were landed from the steamer Atua at Chelsea, and brought over to Auckland on the ferry boat by the bo’sun. On landing, the guide took them across the dark locality abutting from the wharf to Little Queen Street, and to near the rear of the promises of Ah Chee. There Sai Louie met them, and when the bo’sun departed they were driven by motor to the ginger factory in Rutland Street, and later taken to the gardens at Mangere, where they had remained until discovered by the police. They had been paid no wages.

“Sai Louie's connection with the matter dated from the time the Atua's mail was landed, when he received a letter. Defendant had told the police that he met the two men in Queen Street, and he merely gave them a job. That was on April 26. After that defendant gave several conflicting statements to the Customs Department. On April 30 he admitted he had done wrong. He said that prior to the Atua's arrival he had no knowledge that the two men were coming to New Zealand, but from the mail that day, he had received a letter requesting him to look after them, which he had done. On May 5 defendant informed a Customs official that he told the two Chinese that they had better return to the Atua, go back to Fiji, and go to school until they could pass the education test and pay the poll-tax. They replied that they could not do this as the Atua was returning to Sydney, where they would be certain to be found as the officials made a strict search there. They also said that if they went back, the bo’sun, from fear of being caught, might throw them overboard at night. They would rather jump from the wharf than go on board again.

“He then took them to the ginger factory, and to the gardens after deciding to give them work. He gave them £10 to buy clothes with. He had nothing to do with ringing-up a relative in Ah Chee's store when the storeman said two men were waiting outside for him at the back of the building. He went out and saw the bo’sun of the Atua, who beckoned him over. He asked the men what they wanted, and then the bo’sun departed. He wrote to Sang On Tie, a big merchant in Fiji, warning him of the seriousness of the offence of smuggling men, and telling him not to do it again as it would ruin his (defendant's) good name in New Zealand, where he had been for 25 years. Besides that, the Chinese here might get jealous of him and get him into trouble. He informed the officials also that he had several times intended to tell the truth, but was afraid. He knew he had done wrong, and intended to ask only for leniency.

“He knew of two other Chinese smuggled in, and he would endeavour to locale them, and advise the officials. He had not received any money for helping the Chinese. Mr. Mays added that defendant, on May 3, again altered his story, saying he did not see the Chinese the night they arrived, but the day alter, and that he intended to plead guilty, but his solicitor later said he was foolish to do so, as he thought he would be able to get him off if he did not know the two Chinese were coming to New Zealand, and if he did not receive part of the £91 paid by the man in Suva. He intimated his intention to plead guilty to aiding and abetting, but not deliberately.”

(Star 6 May)

Sang On Tie in Suva was a businessman with whom the Ah Chee family had business connections. Eventually, Sai Louie was fined a total of £48 12/-. (Star 9 May)

Marine Store (scrap metal) business

Ah Chee was still engaged in accepting scrap metal at his marine store in 1908. In January 1909, he was caught up in a police case against Gustav Solomon, accused of stealing copper cable from the Ponsonby tram barn run by the Auckland Electric Tramway Company. Ah Chee was approached by Soloman to buy the cable in August 1908, with Solomon telling Ah Chee that he had a contract with the tramway company to take their waste copper. Ah Chee bought several lots from Solomon, and in turn off-loaded to another firm. Solomon was convicted. (Star 13 January 1909)

The family fruit and vege business

Ah Chee apparently had premises on Manukau Road, Parnell as at 1906.

A fire broke out in a stable at the rear of Ah Chee's premises, Manukau-road, about ten o'clock last night. The Parnell Fire Brigade were quickly on the spot, however, and reduced the flames before much damage had been done. The extent of the damage to the stable did not exceed £5.

(Star 7/6/1906)

In August 1913, Ah Chee’s flagship store at 11 Lower Queen Street was up for a 6-year lease, the firm apparently having moved out. (Star, 25 August) The business appears to have moved to a new Queen Street address. By December 1914, the business became known as Ah Chee Bros. (Star, 10 December). The main shop’s lease was advertised by William Ah Chee again in 1917.

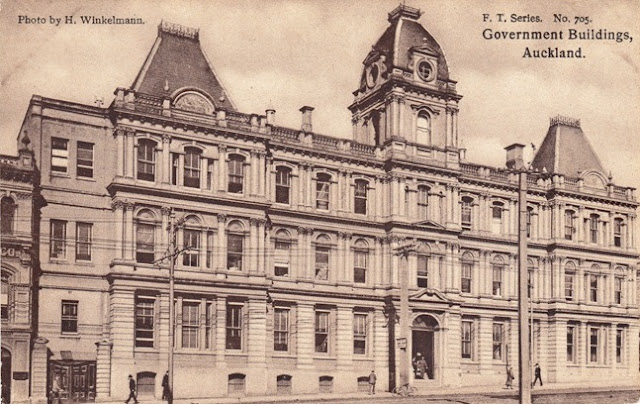

Queen Street, from Quay Street looking toward Customs Street. The Ah Chee family business was on the right side, where today's Downtown shopping mall exists today. Postcard (c.1911) from my collection.

Somewhat ironically, considering the protests from Europeans previously faced by Ah Chee and his fellow Chinese businessmen, Ah Chee was elected to a committee of a fruitsellers association in March 1914 which protested against fruit auctioneers who had signed application papers for Hindu hawkers to obtain licenses. They also called for a rescinding of a Council by-law that fruit sold in the shops had to be covered against dust and flies. (Star 20 March 1914) The firm was fined £1 and costs for a breach of the by-law in May 1915, and again in December that year (20/- and 7/- costs). Clement Ah Chee seems to have been sole Chinese member of the Fruitseller’s Association in 1916.

The Ah Chee family’s fungus business from the 19th century had a slight sideline by 1919: they advertised for mushrooms, “fresh picked”, “highest prices given”. (Star, 17 April 1919)

“The premises in Queen Street in which All Chee started business some forty years ago was a much less imposing building than the fine shop opposite the G.P.O. which is now his headquarters. Two or three assistants were then able to cope with the business that now employs about one hundred hands. Mr. Ah Chee claims that he is the largest fruit and vegetable trader in Auckland, if not in New Zealand. He transacts a large retail business, a big wholesale trade, and carries on an extensive shipping connection: while the fresh vegetables and fruit that appear on the tables of many hotels, boarding houses, and public institutions come from the gardens owned by Ah Chee.

“He grows the greater part of his huge supplies in his own gardens, which cover some two hundred acres through the suburbs. These gardens supply his shop daily with immense quantities of fruit and vegetables, ensuring the freshest goods. The local markets supply him with such produce as does not come within his scope, while every Island boat that comes to Auckland brings great cargoes of oranges, bananas, and pineapples for his store. Australia also yields some of her choicest fruits to his market.

“An interesting side-line, within Ah Chee's scope, is the gathering and the export of fungus. This vegetable matter, to be found in decaying forests throughout the country, has more honour outside New Zealand than within it; it is highly valued in China as an article of food. Although great quantities of this toothsome dainty are exported to China every year, the supply does not cope with the demand, and Ah Chee is anxious to buy as much as he can. He claims, further, that he exports as much as 80 per cent of the total fungus export of New Zealand every year. His prices, too, are well-known amongst many Maoris in the North Auckland peninsula, who say that he pays more for his supplies than any other merchant with whom he has dealings. Farmers and settlers, too, do not disdain to pack up and send to Ah Chee any fungus that they may run across in their travels.”

(Star, 18 December 1920)

From 17 March 1921, Ah Chee & Co took over the lease, at an annual rental of £325, of part of the Auckland City Market site at Sturdee Street, after Turners & Growers surrendered their lease over the site back to the City Council. (Public notice, Star, 1 October 1921)

November 1922 is the first sighting or advertising for an Ah Chee fruit and vegetable store at Newmarket “at Railway Entrance, Broadway”. (Star, 28 November)

During the 1923 Auckland Summer festival at Calliope Dock, Clem Ah Chee provided a “special Chinese junk” upon which “a Chinese orchestra will be stationed to render ‘romantic’ music, and which heads the procession across.” (Star, 19 March 1923)

In August 1923, 688 acres of land at Marua near Whangarei owned by William Ah Chee and Ivan Black from Matamata was sold at mortgagee auction. (Star, 3 August 1923)

The Ah Chee family take to motoring

The first report showing that members of the Ah Chee family had shifted from 19th century to 20th century means of personal transportation came in November 1913 when William Ah Chee was fined 10/- and costs “for motoring round the Queen and Customs Streets corner at more than a walking pace.” (Star, 3 November) He was fined in April 1916 10/- and 7/- costs “for leaving his motor car unattended in Queen Street for more than quarter of an hour.” (Star, 4 April) In October that year, it was Clement’s turn before the bench, caught in a police speed trap along New North Road along with 30 other motorists on an Avondale race day, he was convicted of travelling at up to 42 mph, and fined £2 and 7/- costs. (Star, 11 October 1916)

William Ah Chee appeared again before the court in January 1918 for not sounding his horn on approaching the corner of Queen and Customs Streets (Star, 17 January).

Ah Chee Bros. entered a Hudson motor car in the 1921 New Zealand Motor Cup race at Muriwai Beach (Star, 1 March). William Ah Chee won a stock car race at Muriwai 5 March 1921, and Clem Ah Chee came third out of four in the cup race. For the races at Muriwai in February 1922, the Ah Chee brothers used a Cadillac as well as a Hudson. The Ah Chees made several appearances at Muriwai during the 1920s.

Meanwhile, William Ah Chee’s traffic violations continued.

“William Ah Chee, the well-known Chinese merchant, pleaded not guilty at the City Court this morning when charged with two breaches of the traffic regulations—having permitted a cut out to be used in the motor car he was driving along Manukau Road on the 7th inst., and with driving his car in a manner dangerous to the public. As this was by no means the first time that Ah Chee had been prosecuted for offence against the traffic regulations, considerable interest was manifested in his case. The defendant did not employ a solicitor, but argued his own case.

“The evidence of police witnesses state that the car was making noise like an aeroplane, and that he was driving at a speed approximating 40 miles an hour.

“Defendant denied the cut out, there was no unreasonable noise, and declared that his speed had not exceeded 25 miles an hour.

“The Magistrate convicted on the first charge and ordered defendant to pay 15/- costs of prosecution. On the charge of dangerous driving a conviction was also recorded, and Ah Chee was fined £5, with 15/ costs, and £1 10/- witnesses' expenses.”

(Star, 26 April 1922)